Point Judith Light Station, Rhode Island, in the 1800s. The lighthouse tower, which is constructed of brownstone blocks, was white until 1899, when the upper half was painted brown. National Archives image 26-LG-14-17.

Captain Joshua Kenney Card here, up at Portsmouth Harbor Light Station in my home town of New Castle, New Hampshire. The cherry trees in Portsmouth are blooming and spring is really here at last. Soon the summer people will be stopping by and I’ll be taking them up in the tower. The lonely months of winter are about over.

Today I want to tell you about a family dynasty of keepers down at Point Judith, Rhode Island, that lasted nearly a half-century beginning in 1862.

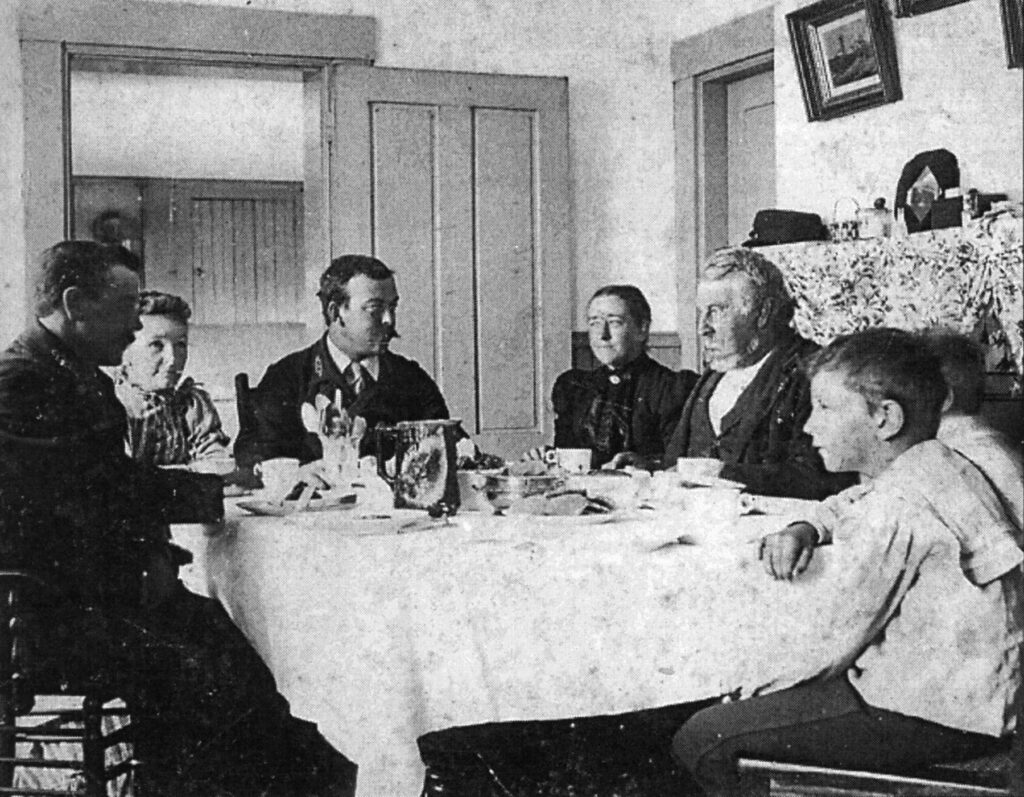

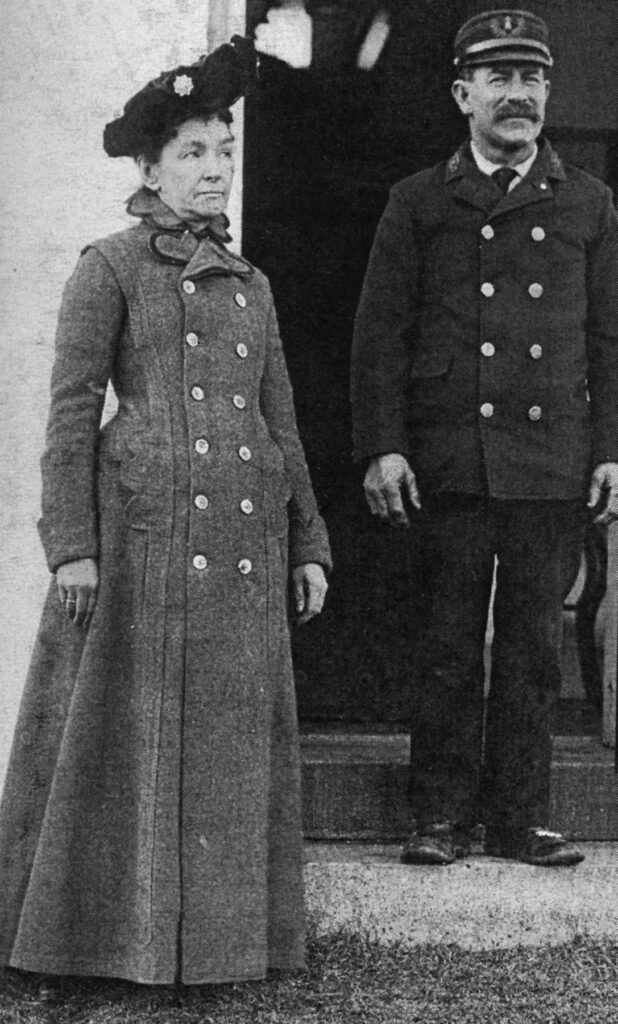

Joseph Whaley – oldest of 11 children and a native of Narragansett, Rhode Island – arrived that year as keeper at a yearly salary of $350. “Captain Joe” and his wife raised three daughters and a son in their 27 years at the lighthouse. Their son, Henry, would become the next keeper in 1889 (at $650 per year), staying until 1910.

An 1889 article in the Providence Journal at the time of Joe Whaley’s retirement at age 70 described his typical duties. The oil lamp needed to be filled after “lighting up” at sunset, then again at 10 p.m., and again at 2 a.m. The clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens needed to be rewound during the predawn hours.

During the day, the weather had to be monitored for the first sign of fog or storm, because the steam boiler for the siren had to be ready for business when visibility was low. Of course, the buildings and grounds had to be kept in top condition, and the brasswork and Fresnel lens had to be immaculate. The keepers also had to cordially show around any visitors to the lighthouse. It was not unusual for 200 or more visitors to arrive on a summer afternoon. All in all, the keeper and his assistant had plenty to do “besides basking on the little stretch of green smoking their pipes,” as Joe Whaley put it.

Joe Whaley’s father, Ezekiel, died in 1888 at the age of 96. The 1889 article referred to Ezekiel as the “Whaley of all Whaleys” and said that he had “raised up such a company of sons and daughters that you can’t cast a biscuit in South Kingstown without hitting some of their descendants.”

One of Keeper Joe Whaley’s daughters married Henry W. Clark, keeper at Block Island Southeast Light, and another married Herbert Knowles, the longtime keeper of the nearby Point Judith Life Saving Station that had been established a short distance to the east of the lighthouse in 1876. Henry, Joe’s lone son, became assistant keeper to his father in 1876, when he was only 19 or 20 years old. Henry later served as principal keeper from 1889 to 1910.

The Narragansett Times reported on the astounding number of vessels seen passing Point Judith from June 1, 1871, to June 1, 1872. Keeper Whaley counted 4,444 steamers, 2,183 sloops, 29,757 schooners, 728 brigs, 122 barks, and 23 other ships – numbers that attest to the continued value of the light and fog signal.

The 1872 fog siren equipment was installed in duplicate. If one horn failed, the other would go into service. The 1889 article described the horns as 16 feet long, “tapering from the throat of four inches to the mouth, 30 inches in diameter,” producing a roar that made “the signal house jump” and could be heard “beyond Block Island.”

Sometimes tricks of the weather meant that the powerful signal couldn’t be heard even a short distance from the point. One ship captain complained to the authorities that the siren wasn’t sounding properly, but Joe Whaley pointed out that the district lighthouse superintendent was with him in the signal house at the hour in question, along with a half dozen other people. The vagaries of nature were to blame, not the keeper.

Another episode that may have stuck in Joe Whaley’s craw occurred in 1869, when the brig Meteor went aground west of Point Judith. Herbert Knowles and his lifesaving crew got all the crew and the vessel’s lone passenger safely ashore. According to an article in the New York Herald, Whaley invited the brig’s captain and the passenger to his home, but then threw them out into the cold rainy night when he learned there had been contagious sickness on board the Meteor. The Herald concluded, “Such treatment would not be strange in an uncivilized land, but on our own shores it seems as if such conduct needed something more than a passing rebuke, and ought to be noticed by those in authority.”

Whether this was an accurate account or not, it was in sharp contrast to the report after the steamer Miranda, bound for Nova Scotia, ran ashore west of Point Judith in June 1886. According to the captain of the Miranda, “Light Keeper Whaley and Capt. Knowles were unremitting in their attention to the passengers.” All 40 passengers were safely conveyed to shore and taken to local hotels.

At his retirement, Whaley expressed some resentment about complaints:

You see it is a good deal of responsibility between the light and the fog signal. And I’m getting pretty old to shoulder it all, although my son Henry has relieved me of a good deal of it for years past. Why, every sailor man in the world has his eyes open to catch the lighthouse keepers and complain of them, and they do it every time they get a chance. That is all right, of course, for no one can watch the lighthouses and fog signals in times when they need watching except the sailor who happens to be going by and needs to have everything running all right. They make lots of funny complaints, though. Of course that about the fog signal not running is the most frequent, and I don’t blame them either. But they watch to see whether your light is lit sharp at sunset, and if it goes out sharp at sunrise, and Block Island has been complained of several times for having the light burning after sunrise when it was the sun reflecting from the glass.

Joe Whaley lived out his years at a home in Wakefield, Rhode Island, and died at the age of 88 in 1906. Henry Whaley and his wife, Laura (Stedman), raised three sons at the light station.

****

The preceding is excerpted from the book Lighthouses of Rhode Island by Jeremy D’Entremont, published by Commonwealth Editions, an imprint of Applewood Books, and available from Amazon and other booksellers.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org

Always enjoy these stories. Keep them coming. The idea that lightkeepers lived idyllic lives, which I frequently heard from visitors to our 1860 light in Port Washington, WI, is so far from the reality that you share here.

Thank you.