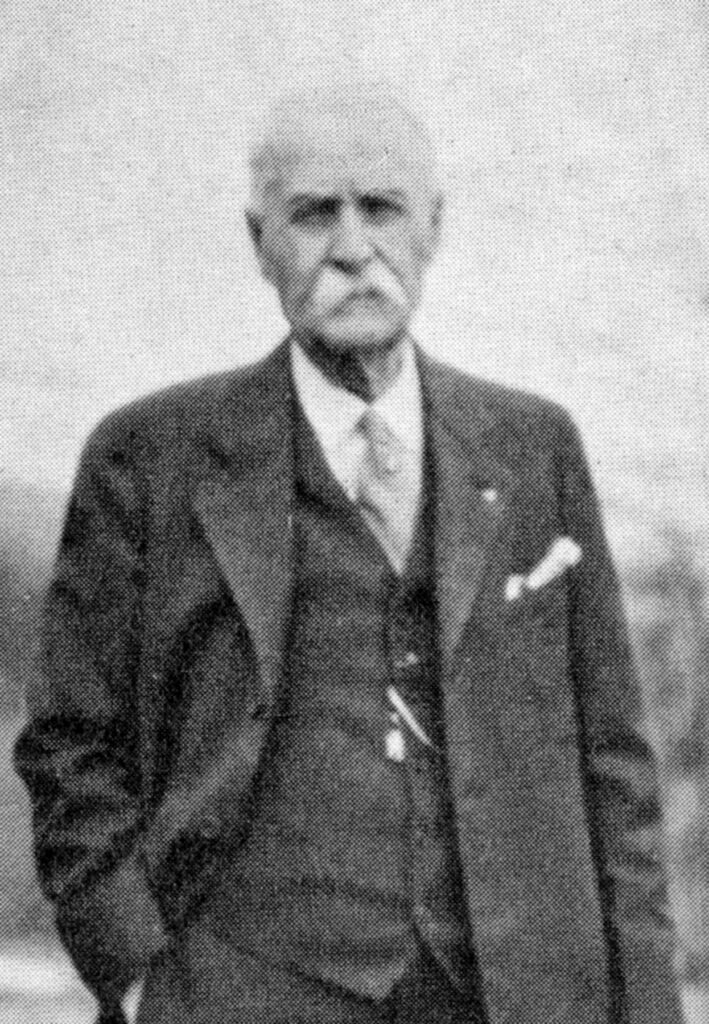

Captain Joshua Card here at Station Portsmouth Harbor. Today I want to tell you about Keeper James Burke, a native of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

James Burke began his career as a keeper, as I did some years earlier, at remote Boon Island, a jumbled pile of rocks some nine miles off the southern Maine coast. He had gone to sea at the age of 14 and eventually skippered fishing vessels before turning to lighthouse keeping.

After a few years as an assistant keeper at Boon Island, 1886 to 1890, Burke became the principal keeper at Burnt Island Light Station in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. Burnt Island, close to the mainland, was a paradise compared to Boon Island. Four years later his next station would be closer to home — White Island or Isles of Shoals Light Station, the southernmost of the Isles of Shoals island group off the New Hampshire seacoast.

Burke was credited with many rescues during his 18 years at White Island. He once helped 16 women whose pleasure boat had capsized near the island. On another occasion, he saved three persons whose boat was sinking fast. He also rescued four crewmen from the Bangor schooner Medford after they had drifted for four days in an open boat.

Burke’s wife shared some thoughts in a newspaper article in May 1905:

I am feeling much better since the beautiful springtime has come. The mornings are delightful here now, the birds are giving their morning songs, and that seems to put new life into one; while the sun, as it peeps out of the sea so early these fine mornings, seems to bring new strength to go forward to aid life’s duties. All through the short days of winter I was kept busy, as we had the assistant to board with us, and my daughter Emma, being away this winter, made more steps for me to take. Since that time I have had three men sent by the government to repair what the sea washed to pieces in the heavy storms of winter. The storms were beautiful to watch from the windows, but little [daughter] Lucy was so afraid that she cried with fright, and I kept her in the sitting room, busy cutting out paper dolls, until the storm subsided. Sheets of salt water would strike the windows and sound like the fiercest hailstorm.

National Archives image 26-LG-2-63

Burke made local newspaper headlines in January 1911 when he kept the light going for six nights through extraordinary circumstances. His wife was ill with pneumonia and the assistant keeper, Gordon Sullivan, was away on shore leave.

Burke also fell seriously ill, but he crawled to the lantern on his hands and knees to keep the light going each night. Burke tried to signal for help, to no avail. When Sullivan returned to the island and found the Burkes in a dire situation, he alerted Captain Joseph Staples of the lifesaving station on nearby Appledore Island. A tugboat was summoned and the Burkes soon received medical attention on the mainland.

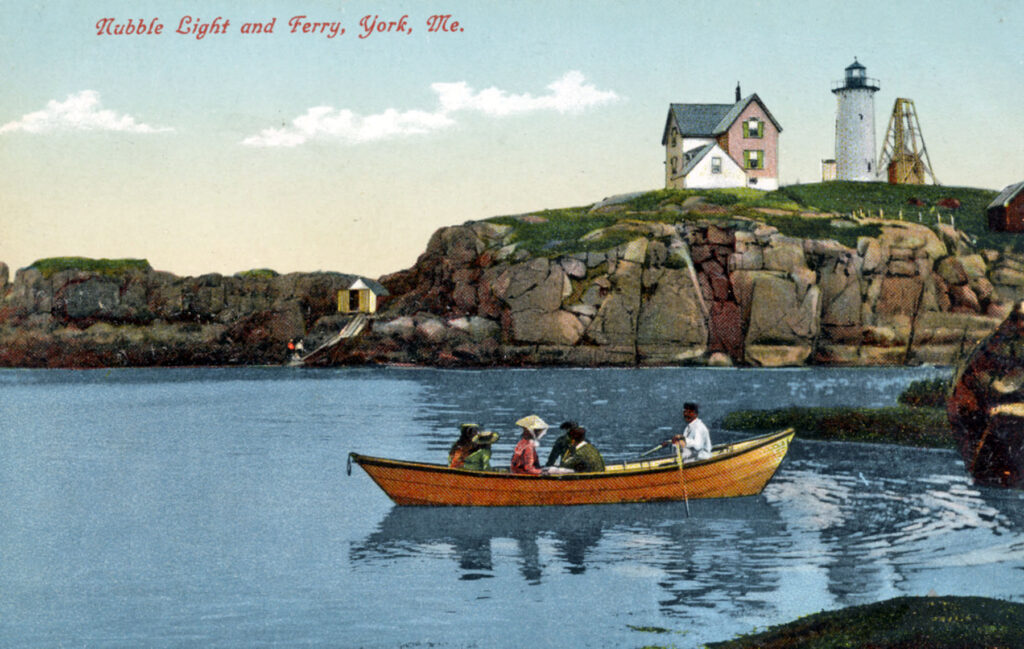

Burke’s final station, starting in 1912, was not far up the coast — the Cape Neddick “Nubble” Lighthouse in York, Maine. By this time, one of his sons, Charles Burke, was keeper at Wood Island Light, just up the coast off Biddeford Pool.

Like many lighthouse families, the Burkes kept a cow and chickens on the island known as the Nubble. Burke went duck hunting and fishing to supplement his family’s food supply. Lobsters, crabs, and mussels were also plentiful near the island. In a letter to author Clifford Shattuck, James Burke’s daughter Lucy Glidden Burke Steffen later recalled other details of life on the Nubble:

We all had lots of work to do, as everything had to be immaculate throughout the house as well as the lighthouse tower. . . . We had lots of company, weather permitting. Many of my schoolmates used to enjoy coming over to the Nubble, some just to spend the day, some to spend the night or possibly to stay for a few days. Sometimes the sea got rough and they HAD to stay. We had an organ in the living room which I used to play and we all had such good times singing the old songs. Our home was a very comfortable six-room house, having a very pleasant living room, a nice size dining room, a large kitchen with pantry, and three bedrooms upstairs. But, of course, no bathroom. We had a large parlor stove which seemed to heat most of the house very well. Even though a severe storm might be blowing up outside, we were nice and cozy.

At low tide, it was sometimes possible to walk between the Nubble and the mainland. Lucy recalled being carried piggyback by her father, who would wear hip boots for the occasion, across the bar. She also recalled the large numbers of birds that would fly into the tower at night; the family sometimes had to rake up hundreds of them that lay dead on the ground in the morning.

James Burke’s second wife died during his stay at the Nubble, and the government provided a lighthouse tender to transport the family to Boothbay Harbor for the funeral. During World War I, the Burkes were joined on the Nubble by military personnel who kept watch for enemy submarines. The light was dimmed on some nights and extinguished on others, to confuse “possible submersibles” in the vicinity.

After he retired in 1919, Burke opened a small fish and bait shop near York Beach. He spent his last summers in York, and winters in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, with his third wife, Fannie. It was a fitting, quiet last chapter for this man of the sea, who died in 1935.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org