Kate Walker here, keeping the light on Robbins Reef, with more on lighthouse architecture.

The light in the tower is what really mattered in a lighthouse. The tower of a lighthouse was there to support the lantern which housed the optic. The light needed protection from the weather and birds and anything else that might fly into it. The protective lantern was typically constructed of cast iron; round, square, octagonal, or hexagonal-shaped; and surrounded by a stone or cast-iron gallery.

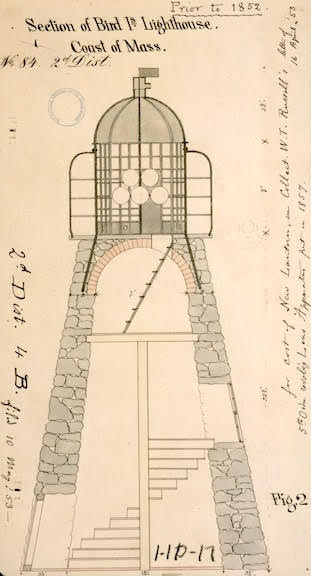

Until the adoption of the Fresnel lens in the United States in the 1850s, there was no uniform design for the lantern. Pre-1850s lanterns are rare and are often referred to as old-style or bird-cage lanterns because of their bird-cage appearance. Selkirk (Salmon River) Lighthouse, New York, built in 1838, retains its bird cage lantern. The bird cage lantern on Cape Henry Lighthouse, Virginia, is a reconstruction of one built in 1792.

Many pre-1850s light towers had their older lantern removed and new cast-iron lanterns installed when Fresnel lenses were added to a light station. Most light stations in the United States were fitted with Fresnel lenses by 1860. In addition to the replacement of the lantern, the tower supporting the lantern was often modified to accommodate the larger lenses.

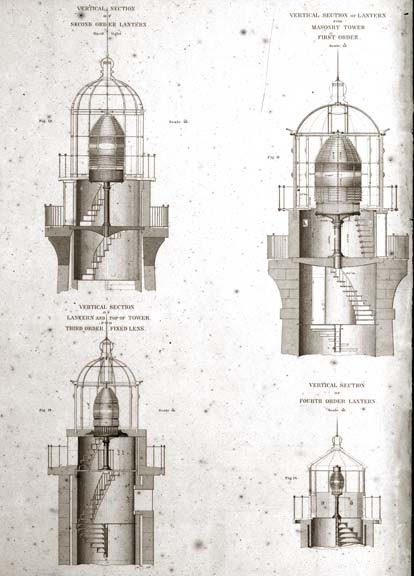

Fresnel lenses were developed in seven standard sizes, depending on need. The largest first-order lenses were designed for important coastal sites while the sixth order, the smallest, was designed for small harbors and rivers. In a new lighthouse the Light-House Board decided what order lens would be used.

To accommodate these new lenses the Lighthouse Board designed four pre-made, ready-to-assemble cast-iron lanterns for first, second, third, and fourth orders. (The fourth-order lantern could accommodate fourth-, fifth-, and sixth order Fresnel lenses.) While it was possible to install a smaller order lens in a lantern of a larger order, it was not possible to increase the lens size for a lantern of a lesser order except for the fifth or sixth. Detailed plans for these cast-iron lanterns can be found in the National Archives, as well as plans for many other lanterns—often the exact plan for the lantern of a specific lighthouse.

Windows in towers were positioned to provide daylight onto the stairs. For taller towers, landings were provided at regular intervals. The top landing ended at the watchroom where the keeper on duty ensured that the light was functioning properly. The lantern room above was usually reached by a ladder.

Information is from the Historic Lighthouse Preservation Handbook.

Submitted by March 14, 2018

* * * * *

U.S. Lighthouse Society News is produced by the U.S. Lighthouse Society to support lighthouse preservation, history, education and research. Please join the U.S. Lighthouse Society if you are not already a member. If you have items of interest to the lighthouse community and its supporters, please email them to candace@uslhs.org.

Candace was the US Lighthouse Society historian from 2016 until she passed away in August 2018. For 30 years, her work involved lighthouse history. She worked with the National Park Service and the Council of American Maritime Museums. She was a noted author and was considered the most knowledgable person on lighthouse information at the National Archives. Books by Candace Clifford include: Women who Kept the Lights: a History of Thirty-eight Female Lighthouse Keepers , Mind the Light Katie, and Maine Lighthouses, Documentation of their Past.