I thought you might like to hear a little about my good friend, William Converse Williams, who was one of the most respected lighthouse keepers in Maine history. During the years I was at Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in New Hampshire, he was just up the coast at remote Boon Island, a miserable little pile of rocks six miles off the southern Maine coast.

Williams (I always knew him as Willie) was a native of Kittery, Maine, and he went to Boon Island as second assistant keeper in 1885. He advanced to first assistant in late 1886, and then became principal keeper on November 21, 1888. He went on to serve 23 years in the position, earning $760 yearly without a single raise.

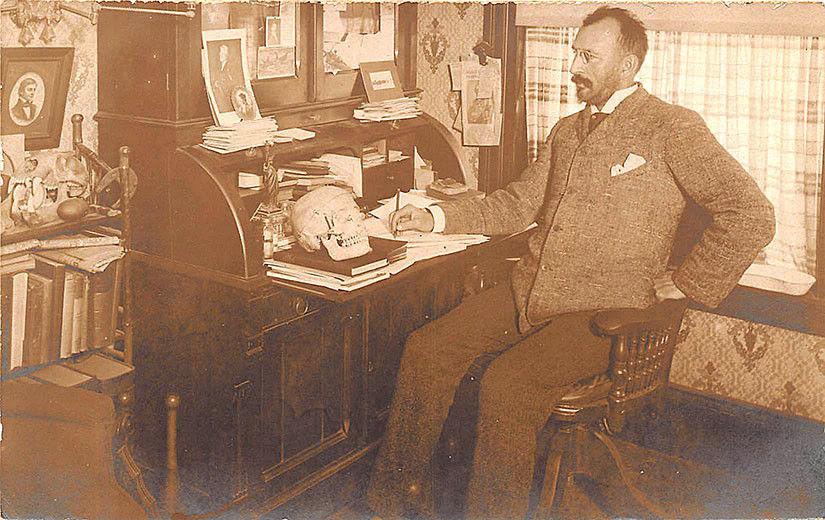

Williams, who worked in construction as a young man, married Mary Abbie Seaward of Kittery. They had three children: Charles, Lucia Mabel, and Bertie (who died in childhood). A 1926 newspaper article described Williams: “He was a tall, spare, man, dignified, and a refined gentleman of the old school. He had a soft, low voice, and his language was marvelous for its simplicity and purity. He had an optimistic disposition, nothing ever worried him and he never got excited. He was neat and methodical even in performing the simplest task.”

At the age of 90, Captain Williams recounted his experiences at Boon Island to Robert Thayer Sterling, author of Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them. Williams had many pleasant times at Boon Island, but he recalled the danger of the job:

There were days when I first went on the station that I could not get away from the idea that I was the same as locked up in a cell. . . . All we had was a little stone house and a rubblestone tower. When rough weather came we didn’t know as it would make much difference as to whether we went into the tower or not, for a safe place. The seas would clean the ledge right off sometimes. It was a funny feeling to be on a place and know you couldn’t get off if you wanted to, and tidal waves was all the talk in the early days. I was a young fellow and had never been placed in such a situation. When the terrible seas would make up and a storm was in the offing, I was always thinking over just what I would do in order to save my life, should the whole station be swept away.

Williams described the experience of keeping watch in the tower during bad weather:

There was no lounging place at the top of the tower, only an old soap box or camp stool for a seat. As you set there [sic] just watching your light, all the enjoyment you got was hearing the wind making a cottonmill din around the lantern. With such a noise and being so many feet up from the ground, the seas battering the rocks down below is utterly drowned out. . . . One can hardly believe that after a storm you would find the big plate glass windows of the lantern covered with salt spray, at that distance in the air. After some storms the spray on the glass would be so thick and dimmed with bird feathers it would require a whole day to clean things up before lighting-up time.

In an 1888 storm, Williams and the others on the island had to take refuge at the top of the lighthouse tower for three days. Compared to this storm, said the keeper, the famous Portland Gale of November 1898 was “just a breeze.” In a January 1896 storm, Williams and his wife again took shelter in the tower as high seas completely surrounded the dwelling.

The Portsmouth Herald published vivid details of another gale that began on January 31, 1898. The temperature was two below zero, and thick ice formed on the lighthouse and other buildings. The ice was so thick that the fires in the stoves inside the dwellings had to be extinguished for a time because the chimneys were blocked. For nearly 24 hours the winds blew at 75 to 100 miles per hour. The seas moved two water tanks, each weighing approximately four tons, about 75 feet. “It was the hardest night we ever passed,” said Williams, “and no one slept on the island the entire night.” Williams called the unusual sight of the island completely encased in ice “one of the grandest sights” he had ever witnessed. The oil house belfry that held the fog bell was so clogged with ice that it took several hours of chopping with axes to get the bell working again.

In my next column I will tell you more about Captain Williams’s amazing adventures at Boon Island.

Submitted by Jeremy D’Entremont, March 19, 2018.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org