Of all the lighthouse engineers in American history, George Meade is perhaps the most famous. Yet he also gets more credit than he deserved.

George Gordon Meade graduated from West Point in 1835, 19th in a class of 56. He ranked immediately behind Montgomery Blair, who was later Postmaster General during the Civil War, and well ahead of Marsena Patrick, Meade’s future Provost-Marshal General. Four of the top five members of Meade’s class resigned from the Army within a year of graduation – not uncommon for the time.

The primary purpose of antebellum West Point was to train engineers and at that it was fairly successful. Meade’s middling class rank belied his engineering ability and resulted in his assignment to artillery instead. He resigned a little over a year after graduation to become a civil engineer. The creation of the Corps of Topographical Engineers (separate from the Corps of Engineers, 1838-1863) necessitated more engineer officers, and Meade rejoined the Army in 1842.

Meade’s involvement in a Delaware Bay survey in 1844-1845 helped lead to his first lighthouse project. He assisted his older brother-in-law, Hartman Bache, with the constructed of the first screwpile lighthouse ever built in the United States at Brandywine Shoal in 1850. This skeletal lighthouse would later be replaced by a caisson lighthouse more resistant to ice flows.

From 1847 to 1849, Meade conducted mapping surveys of the Florida Keys. His familiarity with the area combined with his experience at Brandywine Shoal Lighthouse resulted in his assignment to Florida from 1852 to 1856, first on Special Duty then as the first 7th Lighthouse District Engineer.

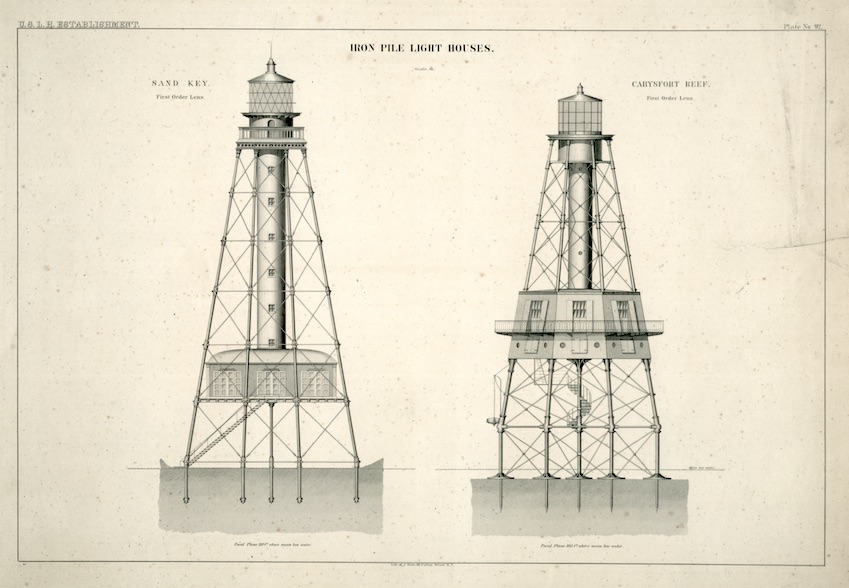

Meade’s first task was completing the Carysfort Reef Lighthouse. Recent research by Neil Hurley shows the lighthouse was actually designed by I.W.P. Lewis and Howard Stansbury. Also, while it is an iron pile lighthouse, the nature of the ocean bottom meant screwpiles were not used. (See Hurley’s Lighting Carysfort Reef, Volume 2 for more details.) Early in the lighthouse’s construction, Stansbury was transferred to a survey project in Utah. His successor, Thomas B. Linnard, died in 1851. Lewis assisted Stansbury and Linnard in supervising the construction at Carysfort, but resigned abruptly from the project. Meade only supervised the completion of the lighthouse in 1852 and, due to legal issues delaying the first-order Fresnel lens, its lighting with Lewis Lamps. Carysfort is now the oldest surviving iron pile lighthouse in the world.

(National Archives drawing, U.S. Lighthouse Society archives)

Next Meade took over the Sand Key Lighthouse project from I.W.P. Lewis, who was also that tower’s designer. The square-based iron pile lighthouse is the only one of the six Florida Reef Lights to use screwpiles, being built on a low-lying sandy islet rather than the coral reef.

Here Meade not only supervised more of the project, but made alterations. Sand Key does not use its original lantern design, but instead one distinctive to some of Meade’s lighthouses manufactured by Merrick of Philadelphia. These lanterns have three rows of triangular glass panes instead of the more common square panes and a cylindrical cupola instead of a round vent ball. A small ledge above the first row of glass and a handrail above the second aided keepers in cleaning the windows and another rail near the outer edge of the roof provided safety there as well. In addition to the new lantern design, Meade successfully tested his new Meade Hydraulic Lamp which he found superior to French-made lighthouse lamps of the era. Sand Key is now the oldest surviving true screwpile lighthouse in the world.

In 1853, Meade located and designed the cottage-style Cedar Keys Lighthouse on Seahorse Key (located on Florida’s “Nature Coast,” not in the Florida Keys), the shortest lighthouse tower in Florida. The lighthouse was completed in 1854 (with a more traditional lantern), although Meade may not have personally supervised construction.

In 1854, Meade located and designed a brick lighthouse for Jupiter Inlet, but construction was delayed. Jupiter’s design was modified by Meade’s successor, William F. Raynolds, and that lighthouse was completed in 1860. Meade designed an extension for the Cape Florida Lighthouse, completed in 1855. Jupiter and Cape Florida both use the same lantern design used at Sand Key.

(National Archives drawing,

U.S. Lighthouse Society archives)

Meade also designed a screwpile cottage lighthouse for Key West’s Northwest Passage and an unlighted daybeacon for Rebecca Shoal (between Key West and the Dry Tortugas). Meade did not personally supervise either project. Northwest Passage was completed without much difficulty, but rough weather at the open-water conditions at Rebecca Shoal repeatedly ruined construction efforts and no beacon would be erected there in until 1878. Meade fumed that no “position more exposed or offering greater obstacles” had ever been attempted as the site for a lighthouse or beacon.

Last but certainly not least was Sombrero Key Lighthouse, off what is now Marathon. Originally intended for a spot called Coffin’s Patches, this is the tallest of the six Florida Reef Lights and the only one Meade actually designed, including his signature lantern. The original work was ruined by a hurricane following Meade’s transfer. The lighthouse would be completed in 1858 at a slightly different location called Dry Bank or Sombrero Key.

In addition to his famous work in Florida, Meade was also the Engineer of the 4th Lighthouse District (the New Jersey coast and Delaware Bay) from 1853 to 1856. There he is associated with three brick giants: Absecon, Barnegat, and Cape May. Meade actually tweaked the design for Absecon from the original plan created by his predecessor, Hartman Bache. Meade’s final design was copied for Barnegat and Cape May (at locations chosen by Meade), but modified slight by his successor, William Raynolds. Meade also designed the improvements for Cape Henlopen Lighthouse, a colonial era lighthouse across the mouth of Delaware Bay from Cape May. This included another Meade-style lantern. Alas, Cape Henlopen fell into the bay in the 1920s due to erosion.

(National Archives)

For a year (1855-1856), Meade was also Engineer for the 5th Lighthouse District (Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina), although its unclear if he designed any lighthouses there.

While the Lighthouse Board would have kept Meade around indefinitely, the Third Seminole War interrupted some of the Florida projects. This, along with a promotion to captain, gave the Army an excuse to reassign Meade to a survey project (not lighthouse work) in the Great Lakes. He was still there when the Civil War broke out and was briefly the 11th Lighthouse District Engineer (July-August 1861) before coming east to command a Pennsylvania brigade. George Meade would rise to command the Army of the Potomac, including its famous victory at Gettysburg in 1863.

Josh Liller is the Historian and Collections Manager for Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse & Museum. He also serves as a Historian for the Florida Lighthouse Association. He is co-author of the revised edition of Five Thousand Years On The Loxahatchee: A Pictorial History of Jupiter-Tequesta, Florida (2019) and editor of the second edition of The Florida Lighthouse Trail (2020).

George Meade. Was my great great grandfather.

Wow, that’s a great family legacy. Meade was an important person in American history.

Will Doughton

Are you related to Bertha Meade? She was my grandmother.