(US Lighthouse Society

Digital Archives)

James Chatham Duane was born in Schenectady, NY in 1824. His great-grandfather, James Duane, had been a member of the Continental Congress. He graduated West Point 3rd in the Class of 1848 and joined the Corps of Engineers. His antebellum service included two stints teaching engineering at West Point and two stints with the Company of Sappers, Miners, and Pontoniers (including commanding said company as a 1st Lt. for just over two years just prior to the American Civil War).

From Aug 1856 to Mar 1858 he was 3rd Lighthouse District Engineer, responsible for construction and repair projects on lighthouses in New York Harbor, the Hudson River, Long Island, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. The two most notable projects during this time were the construction of Shinnecock and Fire Island Lighthouses on Long Island. Design work for the former was already finished by the time Duane entered duty, but he deserves credit for the latter. According to the NPS Historical Structure Report, Fire Island Lighthouse “is primarily the product of Lt. Duane’s efforts. He prepared the drawings, procured most of the materials, and saw the work begin.”

In the early days of the Civil War, Duane assisted in the defense of Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida. He declined a commission as Captain in the 12th Infantry, preferring to remain an engineer. Duane organized the an Engineer Battalion for the Army of the Potomac and commanded it during the Peninsular Campaign in the spring and summer of 1862. He was promoted to Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac for the Antietam Campaign. Also during 1862 Duane wrote Manual for Engineer Troops, the standard engineering manual for the Union Army for the rest of the war.

Duane was transferred to the Department of the South in November 1862 to serve there as Chief Engineer. After the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, Major Duane was recalled to Virginia to served as the Army of the Potomac’s Chief Engineer for the remainder of the war. He served in that capacity for the rest of the war, rising to Brevet Brigadier General.

early 1900s postcard

(US Lighthouse Society Digital Archives)

After the war, James C. Duane worked on various engineering projects in the northeast. This included 1st Lighthouse District Engineer (1868-1879), 2nd Lighthouse District Engineer (1870-1881), and 3rd Lighthouse District Engineer (1878-1886).

There was a great deal of lighthouse construction in New England during Duane’s time there. Most notable were the cylindrical brick-lined iron towers. The first three varied widely in size and style. Fort Pickering Lighthouse was a short, simple tower built in 1871. Next came the twin lights at Cape Elizabeth, Maine, completed in 1874. They were not only the tallest of these lighthouses but also the only ones with large lanterns, originally using 1st and 2nd order Fresnel lenses. Along with their stacked windows and the style of the stairs and landings, these twin towers were probably designed by Paul Pelz, Chief Draftsman of the Lighthouse Board. If in fact Duane designed them himself, he must have been heavily inspired by the Pelz standard brick design in wide use at the time. The next year, the Portland Breakwater “bug light” was built. Although only 30 feet tall, it has several ornate exterior features, including Corinthian columns. The design is usually credited to Thomas Ustick Walter, a Philadelphia architect.

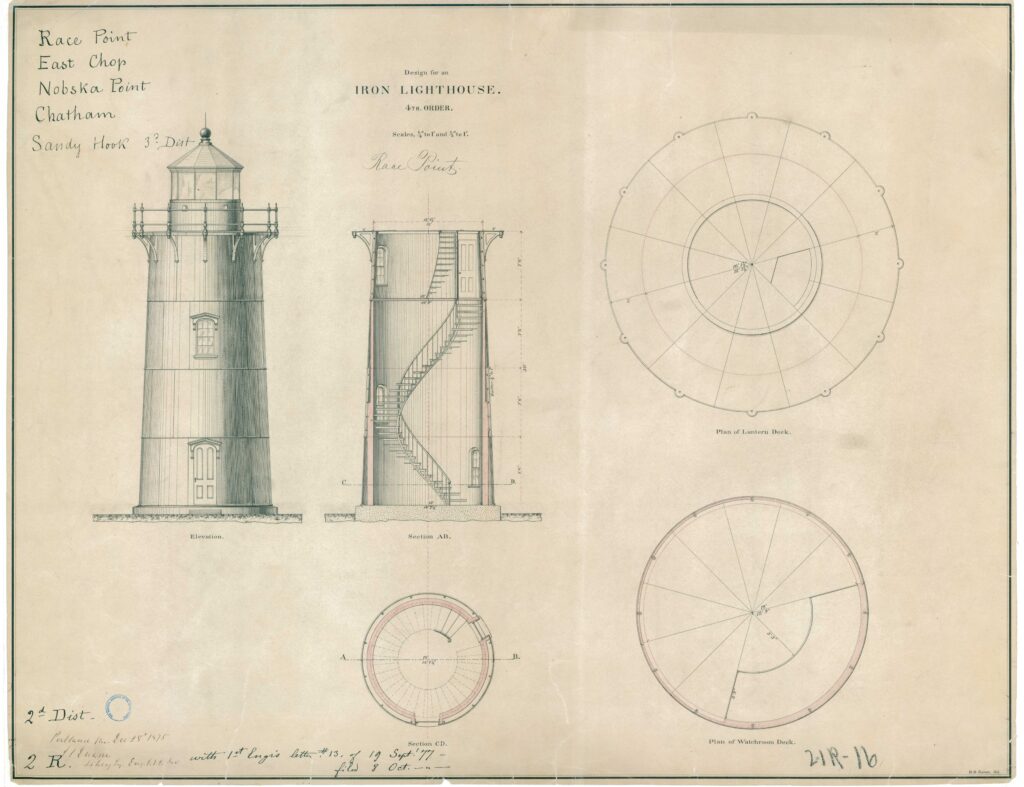

Fort Pickering, Cape Elizabeth, and Portland Breakwater apparently influenced the creation of a standardized design used on at least a dozen lighthouses in the northeastern United States. As the design was used exclusively when Duane was district engineer it seems likely it was his creation and probably warrants the style being called “Duane Towers.” This standard design had four windows at different heights and directions, portholes near the top of the tower, and no landings for the stairs. Lighthouses of this design were nearly all between 40 and 50 feet tall with fourth-order Fresnel lenses. Built between 1876 and 1881, known Duane Towers are: Cape Neddick (Nubble) and Little River, Maine; Portsmouth Harbor, New Hampshire; Race Point, Nobska Point, Chatham Twin Lights (north light later moved to Nauset), Ipswich Rear Range (later moved to Edgartown), Mayo’s Beach (later moved to Point Montara, CA), and East Chop, Massachusetts; Stratford Point, Connecticut; and Sandy Hook East Beacon, New Jersey. Half of these lighthouses were replacements for older masonry towers.

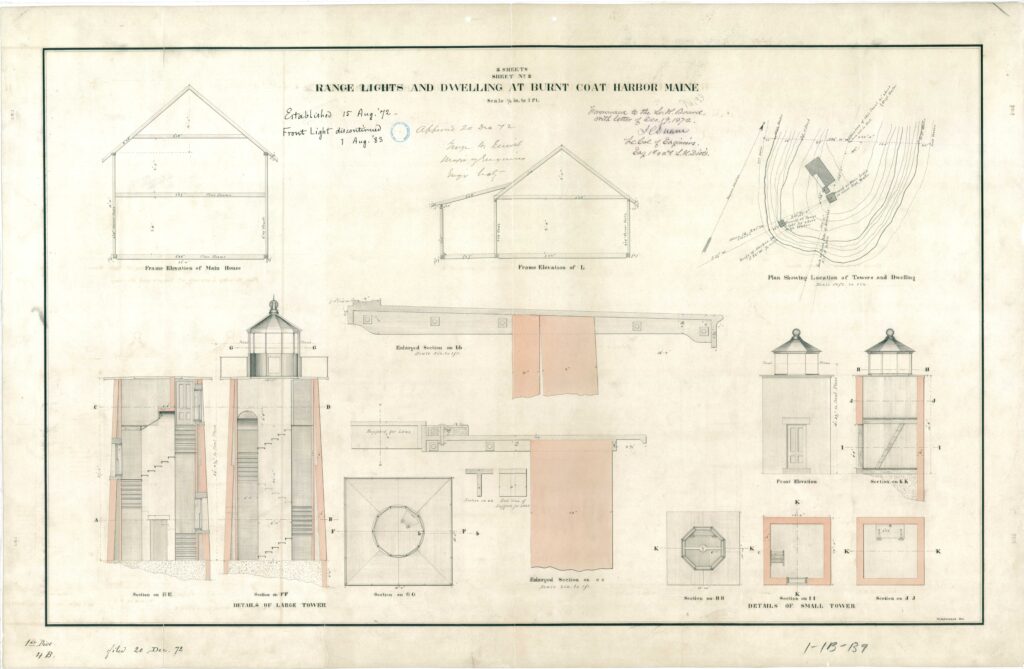

Duane built more than just cylindrical iron lights. He designed the stone 1872 Whaleback Lighthouse which is located in southern Maine but at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbor, New Hampshire. Avery Rock and Egg Rock were both built in Maine in 1875. Each was a square brick tower surrounded by a keeper dwelling, using a design by Duane with slight modifications by the Lighthouse Board. Duane also designed the free-standing square pyramidal Burnt Coat Harbor Lighthouse (1872), and probably the Grindel/Grindle Point and Indian Island square brick towers a couple years later.

Besides his postwar lighthouse work, Duane wrote formal papers for the Army about bridge equipage, a subject upon which he seems to have become an expert as a result of his experience before and during the Civil War. Duane was the U.S. Army’s Chief of Engineers during the last two years of his career (1886-1888), in which capacity he was also a member of the Lighthouse Board. After retiring from the Army at age 64, Duane was Commissioner of the Croton Aqueduct in New York City until his death in 1897.

Josh Liller is the Historian and Collections Manager for Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse & Museum. He also serves as a Historian for the Florida Lighthouse Association. He is co-author of the revised edition of Five Thousand Years On The Loxahatchee: A Pictorial History of Jupiter-Tequesta, Florida (2019) and editor of the second edition of The Florida Lighthouse Trail (2020).