Kate Walker here, tending the light on Robbins Reef.

Once a year a lighthouse tender brought six tons of coal to burn in my stoves, a few barrels of oil for the lamps I put in the lantern every night, and a pay envelope. The tenders regularly brought supplies and workmen to make repairs, and the district inspector. My tenure at Robbins Reef was supervised by four inspectors: Inspector Commander Henry F. Pickering from 1890-1895; Inspector Commander A.S. Snow from 1895 to 1912; Inspector Commander C. D. Stearns for first six months of 1912; and in June 1912 Inspector Joseph T. Yates, the first civilian inspector, who served through the rest of my term in 1919.

Lampists visited every light in their charge at least once a quarter, to accompany the inspector during his tour of inspection, should he require their services, to visit and remain several days at those lights to which new keepers had been appointed, and made frequent inspections of the steam fog-signal in their charge.

The inspector visited all the stations in his district and reported on repairs needed to the tower and buildings; needed renovations and improvements; condition of the station, lantern, illuminating apparatus, and related equipment. Comparisons were made of the interval of flashes and eclipses and their duration, with the intervals given in the Light List. The inspector was responsible for making sure the keeper understood the printed instructions for operating all equipment and other attendant duties. The inspector also reviewed the keeper’s journal and records relating to expenditures, shipwrecks, and vessels passing. The inspector assessed the attention of the keeper to his duties, and his ability to perform them well. Both inspectors and engineers had authority to dismiss a keeper or other employee found in a state of intoxication.

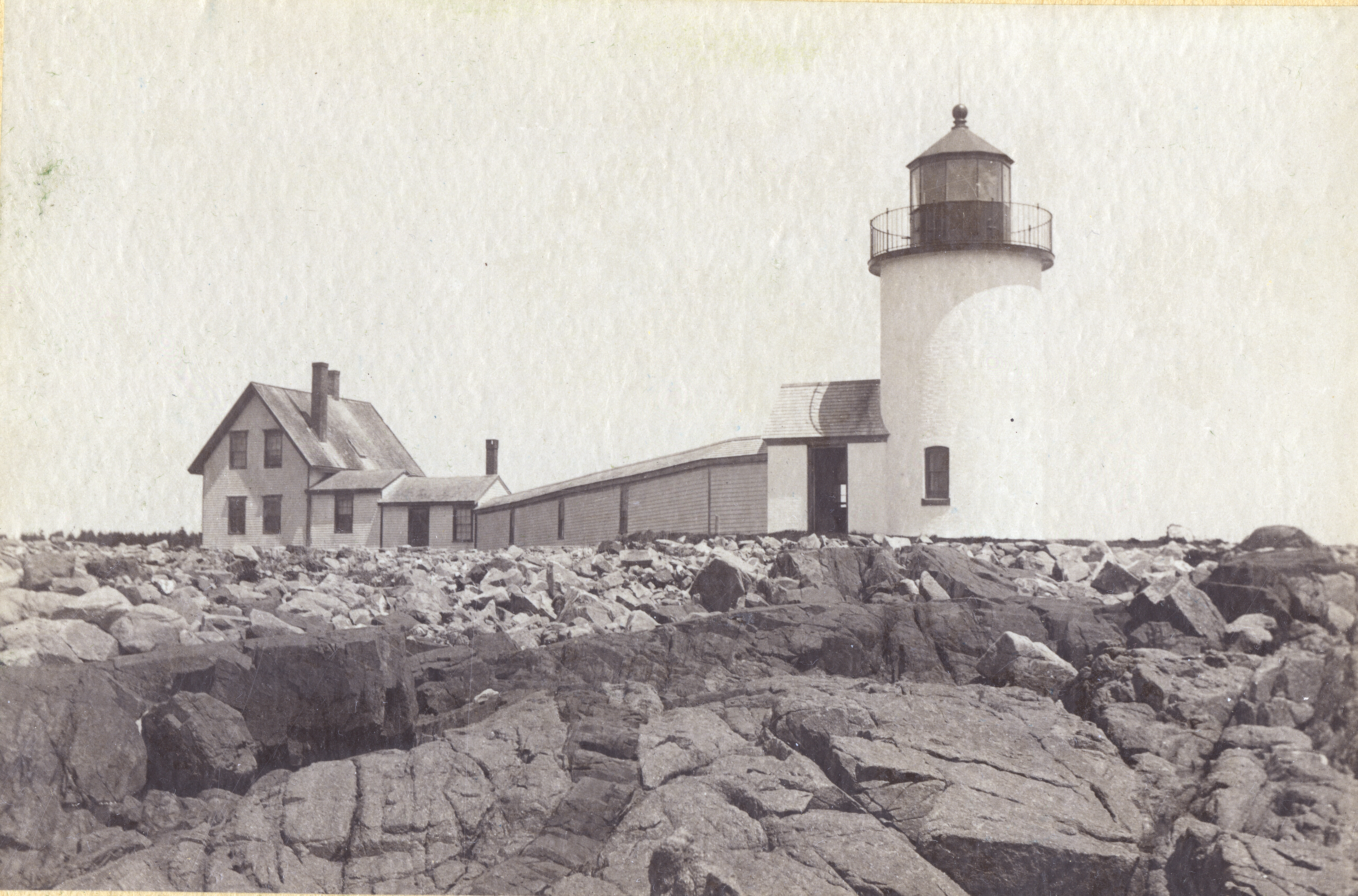

On August 11, 1887, the Inspector of the 1st Lighthouse District reported that he had inspected Goat Island Light Station, Maine, on July 6, 1887, and found it in an indifferent condition, its dwelling being dirty from top to bottom. The Inspector directed the Keeper s attention to his neglect of duty and instructed him to improve the condition of his station.

When a second inspection was made, the whole station was found in a dirty condition. The lantern and tower appeared not to have been swept or dusted for weeks; the lens was covered with lint and dust, the reflector was dirty and the plate glass of the lantern was streaked with dust and spotted with fly specks. The dwelling was filthy — “offensive,” the Inspector states — to sight and smell. The Board did not consider Keeper John Emerson a competent person for the position he held and asked his removal.

A woman may be more inclined than a man to keep her lighthouse neat and clean. I always looked forward to the inspector s visit because he brought news and told lighthouse stories, which I always enjoyed.

Information is from National Archives Record Group 26, Entry 1, Volume 753; Lighthouse Service Bulletins; U.S. Treasury Department, Organization and Duties of the Light-house Board; and Regulations, Instructions, Circulars, and General Orders of the Light-house Establishment of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871); National Archives Record Group 26 Entry 24 (NC-31); and Clifford, Maine Lighthouses, p. 160.

Information is from National Archives Record Group 26, Entry 1, Volume 753; Lighthouse Service Bulletins; U.S. Treasury Department, Organization and Duties of the Light-house Board; and Regulations, Instructions, Circulars, and General Orders of the Light-house Establishment of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871); National Archives Record Group 26 Entry 24 (NC-31); and Clifford, Maine Lighthouses, p. 160.

Candace was the US Lighthouse Society historian from 2016 until she passed away in August 2018. For 30 years, her work involved lighthouse history. She worked with the National Park Service and the Council of American Maritime Museums. She was a noted author and was considered the most knowledgable person on lighthouse information at the National Archives. Books by Candace Clifford include: Women who Kept the Lights: a History of Thirty-eight Female Lighthouse Keepers , Mind the Light Katie, and Maine Lighthouses, Documentation of their Past.