Captain Joshua Card here, up at Station Portsmouth Harbor in New Hampshire. Full blown summer has arrived, hot and humid and thick a fog some days. I’ve had to wind the striker for the fog bell quite a few times lately.

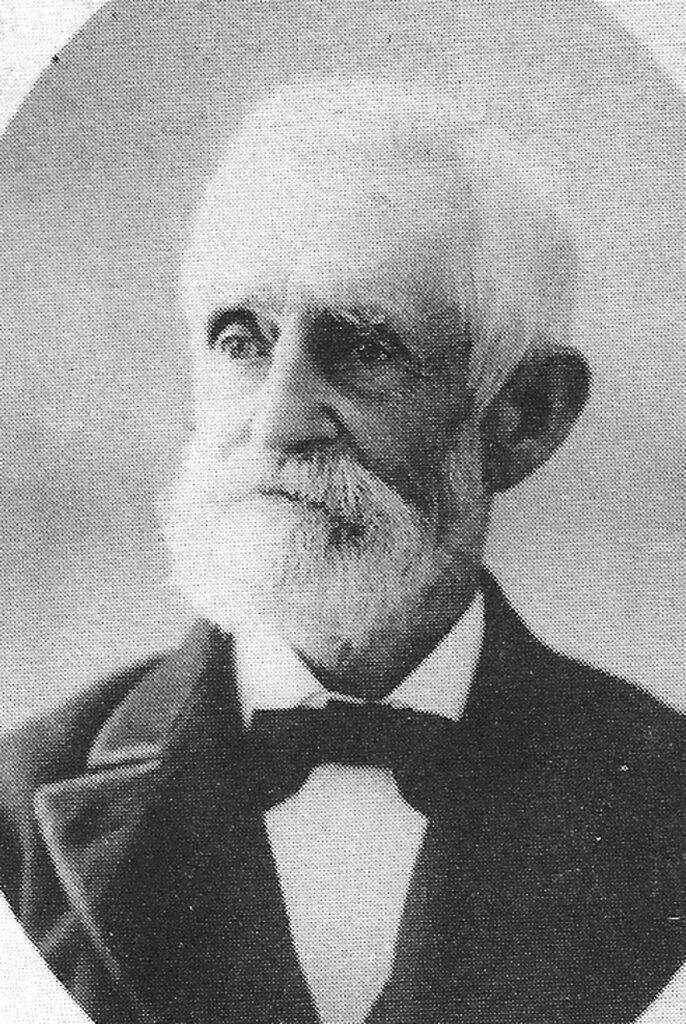

I want to tell you about a keeper down on Long Island Sound, Captain Oliver N. Brooks, whose career started a bit before mine. Brooks became one of America’s most revered keepers of the nineteenth century.

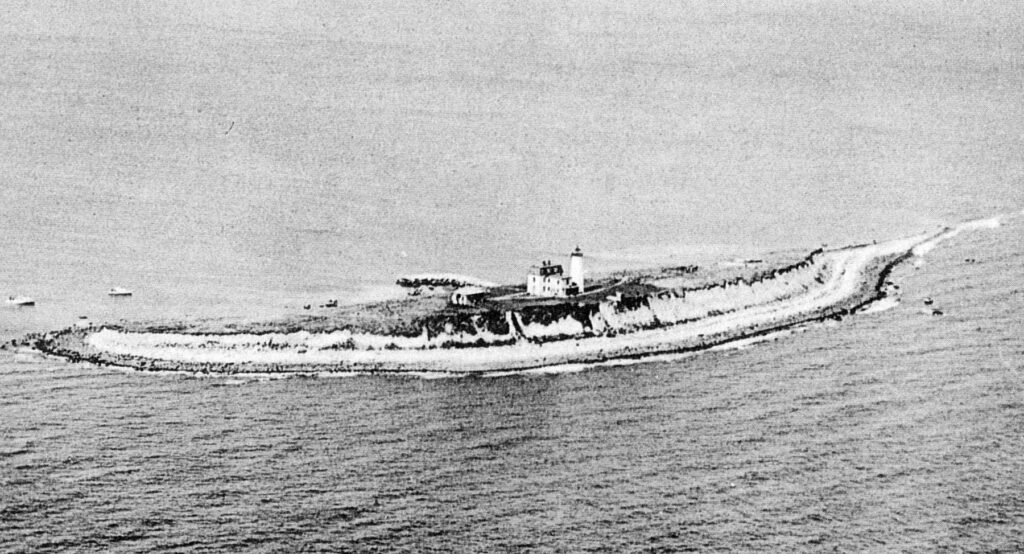

A native of Westbrook, Connecticut, Brooks had first gone to sea as a cabin boy at the age of 13 and became captain of a vessel at 21. He and his wife Mary had their first child in 1849, and when Captain Brooks learned of the pending retirement of Eli Kimberly at Faulkners Island Light Station in Guilford, Connecticut, in 1851, when he was 28, he decided it was time to “settle down” to the relatively stable life of a light keeper.

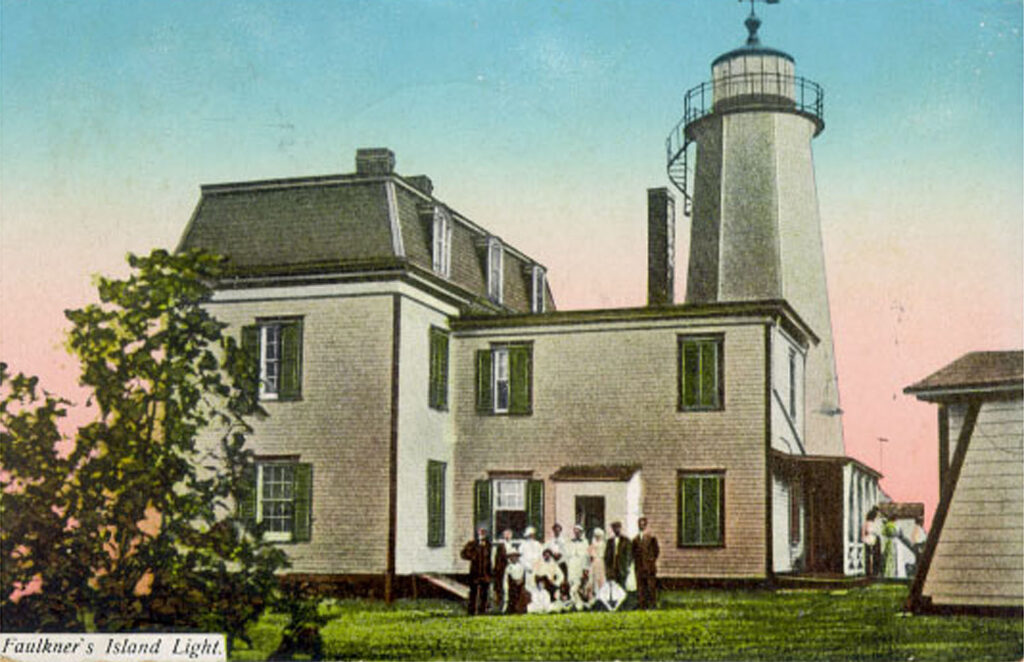

Brooks’s first few years on the island were eventful. In 1856 a new fourth-order Fresnel lens replaced the multiple lamps and reflectors, and in 1858 a new dwelling replaced the earlier one, which was described in the annual reports of the Lighthouse Board as dilapidated and unworthy of repair.

A daring rescue on November 23, 1858, by Keeper Brooks gained him widespread fame. A newspaper described the events:

The recent, courageous and even desperate act of Capt. Brooks, keeper of the Faulkner’s Island Light, in rescuing the captain, his wife and crew, from a wreck in Long Island Sound, deserves more than a passing notice. . . . The wreck lay upon Goose Island, some two miles from this; but Capt. Brooks could see, with his glass, the persons in the rigging, and the sea lashed into unusual fury, making a breech high over its decks, and threatening instant destruction. It was too sad a sight for the brave man to endure, and provided as he was by the government with nothing but a small sailboat . . . he would have been fully justified in leaving them to a fate horrible to think of. His wife was on shore, and he was alone with his family of little children; but telling them of the peril he was about to assume . . . from which he might never return, he kissed them, and calling upon God to protect them and bless his endeavor, he jumped into the frail skiff and steered boldly into the storm and billows.

The five people on the wrecked schooner, the Moses F. Webb from New Brunswick, saw Brooks approaching but felt their situation was hopeless. The newspaper account continued:

By the most skillful management of his boat, now shooting past, and once over the very wreck itself, he at last managed to pick them off, one at a time, and then turned for the shore. But it was only by constant bailing and tremendous efforts that the boat was kept above water, and at last reached the island, with its inmates exhausted, and nearly dead with hunger and exposure.

Brooks’s two small daughters Mary Ellen and Nannie (Nancy Amelia) greeted him with “tears and screams of joy,” and the weary survivors were taken to the dwelling to rest. Sadly, about half an hour before the keeper arrived on the scene, the three-year-old daughter of the vessel’s captain slipped from his grasp and was lost. But the others clearly owed their lives to the courageous keeper. The rescue was cited by many as one of the most daring and miraculous in memory, and for his trouble Brooks received a gold medal from the New York Life Saving Benevolent Association. He also got a raise in pay from $350 yearly to $500, thanks to the efforts of an admiring congressman.

From the collection of Jeremy D’Entremont

During their years on Faulkners Island, the Brookses were warm hosts to government officials and tourists alike. One frequent guest was Professor Joseph Henry, the first chairman of the Lighthouse Board that was created in 1852 and first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Henry and Brooks became close friends.

Brooks was an avid hunter and an expert taxidermist. Over the years, the parlor of the keeper’s dwelling came to be filled with dozens of beautifully displayed stuffed birds. Many of the birds died in collisions with the lighthouse lantern, not an uncommon occurrence at many light stations. During spring and fall migrations, hundreds of birds were sometimes killed in a night.

Brooks’s oldest daughter, Mary Ellen, amassed a collection of beautiful aquatic plants; her books of preserved specimens sometimes fetched $100 or more from collectors. Mary Ellen was also an accomplished watercolor artist. Like her father, she was a daring boat handler and a strong swimmer, and she sometimes assisted her father in rescues. In addition to all this, she was a fine musician and part of a small family “orchestra.”

Captain Brooks sometimes played his flute or fife solo, but when the family gathered for musical sessions, he played the double bass. Mary Ellen played cello or violin, and Nannie played the piano. The ensemble was completed by an unlikely singer—a large Newfoundland dog named Old Tige. The dog’s vocalizations were described by one visiting writer as “not the long howls of canine distress; nor yet were they ordinary barks, but a wonderful something in between.”

Once when the automatic fog bell machinery failed and required replacement parts, Brooks rigged a rope from the bell to the house so that Mary and their daughters could ring it while he went to pick up the needed parts. As it turned out, fog necessitated the manual ringing of the bell for 48 hours during the keeper’s absence. In 1879 a powerful new first-class steam-driven fog whistle replaced the bell. The cistern and boilers for the signal were housed in an odd-looking A-frame wooden shed.

Mary Brooks, like all keepers’ wives, played an enormous role in the daily operation of Faulkner’s Island Light Station. This was officially recognized when she was appointed second assistant keeper in 1879. The position was abolished when the Brooks family left in 1882.

After retiring as keeper, Oliver Brooks moved briefly to California before returning to Guilford and serving in the state legislature. He died in 1913 at the age of 90.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org