Captain Joshua K. Card here, over at the Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse in New Castle, New Hampshire. Summer’s nearly over and many of the local summer residents will be leaving with the Labor Day holiday this weekend. Some will stop by for a visit to the lighthouse before they go. I’ll put on my Lighthouse Service uniform for them. I have a little running joke with the summer visitors. They ask me what the “K” on the lapels of the uniform stands for, and I tell them it stands for “Captain.” Of course, they call me Captain Card out of respect anyway. The “K” actually signifies that I am the principal keeper of the station. My station has no assistant keepers. If it did, the first assistant would wear a “1” on his lapels, and a second assistant would wear a “2,” and so forth.

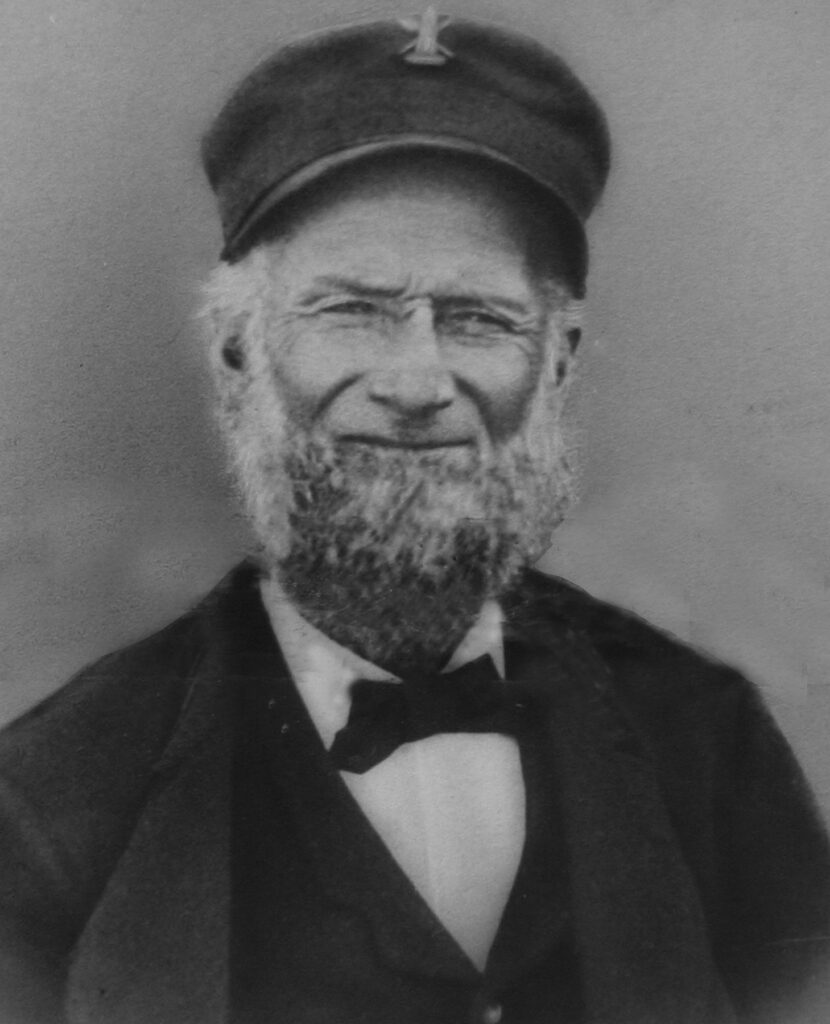

Today I want to tell you about a contemporary light keeper who had a career similar to mine, Joshua Freeman Strout up at Portland Head Light in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. He was born in Portland, Maine, on August 13, 1826. His mother, Jane (Dyer) Strout, had worked as a housekeeper at Portland Head for Keeper Joshua Freeman in the 1820s. She married Daniel Strout, and Daniel and Jane named their first son after Joshua Freeman. Joshua was one of six children.

Joshua Strout went to sea at the age of 11 and served as the cook on a tugboat by the time he was 18. He first served as captain on the maiden voyage of the brig Scotland, built at Benjamin W. Pickett’s shipyard in South Portland. He also owned the Scotland and sailed it for two years as far as Cuba and South America. He captained several more schooners and brigs in the ensuing years. While he was captain of the brig Andres, Strout suffered a severe fall from the masthead. The injuries he sustained forced him to give up his life at sea in exchange for the somewhat more tranquil life of a lighthouse keeper. He became keeper at Portland Head Light in 1869 at a salary of $620 per year, after the previous keeper had resigned.

Strout’s wife, Mary (Berry), a native of Pownal, Maine, was named an assistant keeper at a salary of $480 per year. She held the position until 1877, when her son Joseph took on the title of assistant keeper. Joshua and Mary Strout raised 11 children at the station. Three of their sons were lost at sea during the family’s years at Portland Head.

Although Portland Head was a plum among assignments for lighthouse keepers, life wasn’t always tranquil. A hurricane on September 8, 1869, knocked the fog bell from its perch, nearly killing Joshua Strout. An enclosed, pyramidal tower replaced the old skeletal bell tower in the following year.

The Eastern Argus reported that many people went to Portland Head to view the spectacular surf, and Keeper Joshua Strout “kindly furnished every reasonable facility for the accommodation of the sight seekers.” The sound of the “mountainous billows” striking the rocky shore was described as “a roar like the voice of many Niagaras.”

An African parrot named Billy was a well-known member of the Strout household for many years beginning in 1887 when he was presented to Joshua Strout. Billy heard the keepers, in times of poor visibility, call to each other, “Fog coming in; blow the horn!” One day, when a sudden fog enveloped the station but nobody noticed, Billy cried out, “Fog coming in; blow the horn!” Billy became an avid fan of radio in his declining years and was said to be nearly 90 years old when he died in 1942.

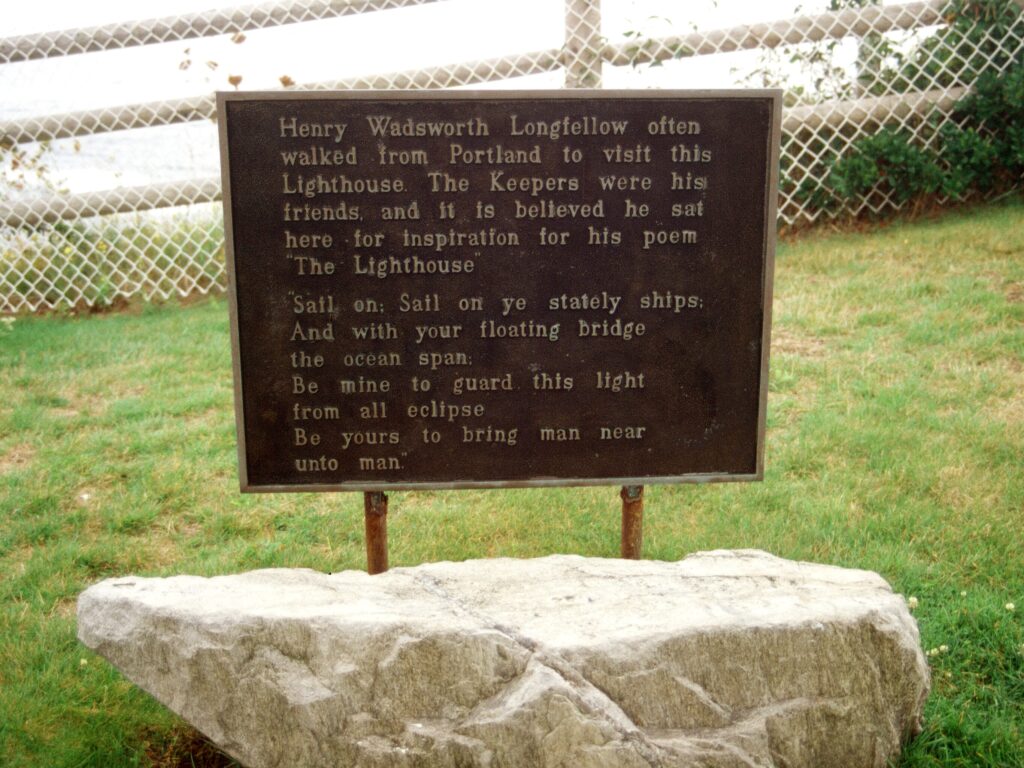

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, beloved American poet, was born in Portland, Maine, in 1807. It’s generally believed that he had visited Portland Head Light, which was about five miles from his childhood home, by the 1840s, and that it served as an inspiration for his 1849 poem The Lighthouse. He lived much of the time in Cambridge, Massachusetts, after 1836. Later in life, Longfellow visited Portland often, and it was not unusual for him to walk to Portland Head Lighthouse. Robert Thayer Sterling, who was a keeper in later years at Portland Head as well as an author, wrote that the poet would bow as a salute to Keeper Joshua Strout, and would then “scan the ocean and its shores.” John Strout, a descendant of the Strout family of keepers, has written, “Longfellow would sit with Joshua, and both would chat and sip cool drinks prepared by my great grandmother.”

The bark Annie C. Maguire entered Casco Bay at about 11:00 p.m. on Christmas Eve, 1886, with the intention of riding out the bad weather in Portland Harbor. A heavy sea was visible outside Portland Harbor that day, as a winter storm was raging offshore. At Portland Head Light, a few miles from the harbor’s entrance, Joshua Strout was asked by a sheriff’s officer to keep an eye out for the ship, in case the captain decided to duck into Portland Harbor to take shelter from the storm. Newspaper reports in the following days said that “rain was falling in torrents.” Joshua’s son, Joseph Strout, assistant keeper at the time, claimed it was windy but not raining.

At about 11:30 p.m., as Joshua Strout kept watch in the lighthouse tower, Joseph was preparing for bed. Joshua later recalled that he heard the shouts of crewmen aboard the Maguire as they tried to veer away from the rocks. Captain O’Niel later said that he could see the light from the lighthouse, but his helmsman misjudged the distance to the light because of the storm. Suddenly, Joshua burst through the door of the keeper’s house and exclaimed to his son, “All hands turn out! There’s a ship ashore in the dooryard!” Joseph fumbled as he put his socks and shoes back on, and then bolted down the stairs a half-dozen at a time.

When he emerged from the house, Joseph Strout was amazed to see the ship on the ledges no more than 100 feet from the lighthouse tower, listing to one side. As soon as it had run onto the ledge, the captain had the crew take down the sails and lower the anchors. According to some accounts, Mary Strout shed light on the scene by burning blankets that had been cut into strips and soaked in kerosene. A newspaper account in the Boston Globe stated that the Strouts put a ladder across to the ship, and that all aboard made it safely across the ladder to solid ground.

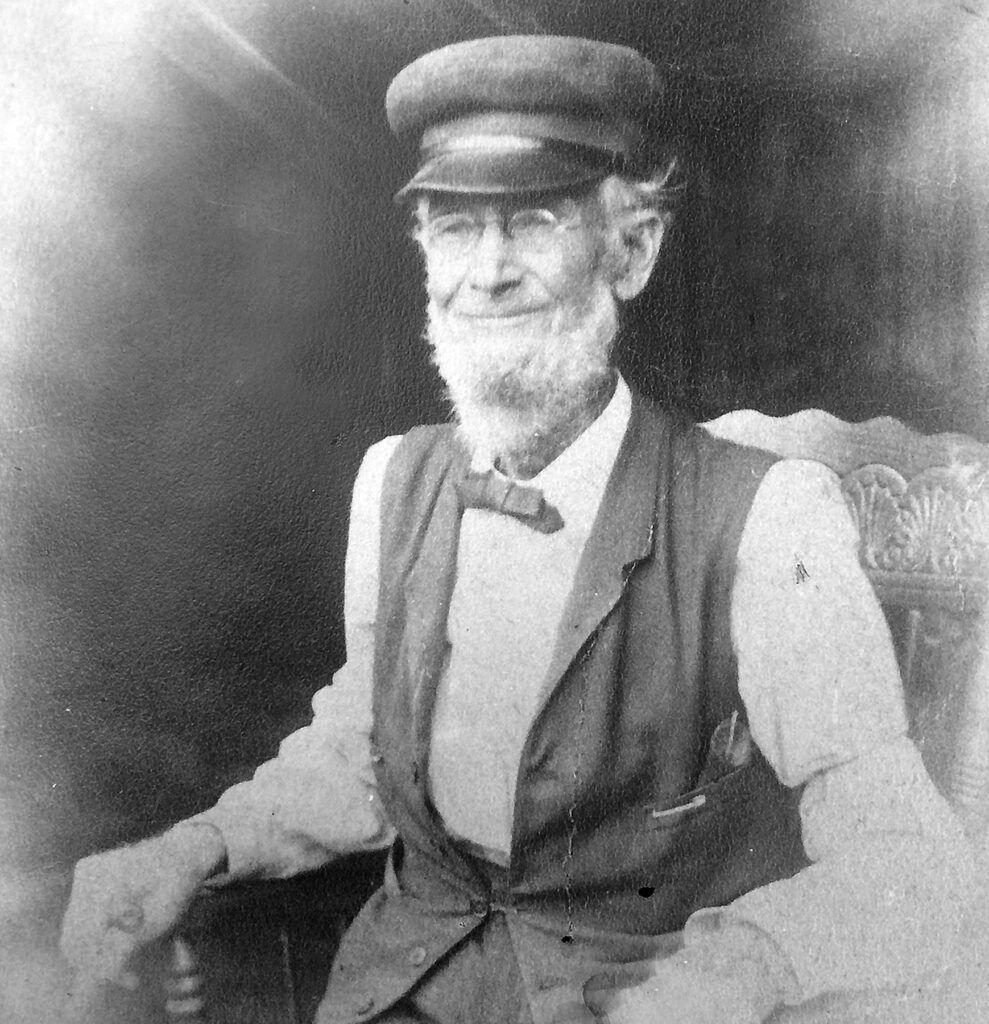

In an 1898 interview, Joshua Strout said that he had gone as long as 17 years in a stretch without taking time off, and as long as two years without going as far as Portland. Strout, the oldest keeper on the Maine coast at the time, retired in May 1904.

His son, Joseph, who was an assistant under his father beginning in 1877 when he was 18, became the next principal keeper. He remained in charge for another 24 years.

Joshua Freeman Strout died at the age of 80 on March 10, 1907, and was survived by his wife of 56 years. He is buried in the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in South Portland.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org

Thank you for this very interesting article on Captain Strout. His wife, Mary Ellen Berry was the sister of my Great X 2 Grandfather, Charles Morris Berry. I am fortunate to have a notebook containing published letters from one of Charles’ sons which tells of his visit from Yamhill County, Oregon to Portland Head Lighthouse and his Uncle Joshua Freeman Strout in 1894.

Thank you for your interesting comment, Patrick. There’s a lot more about the Strouts in my book, “All About Portland Head Light.” I would be very interested to see that letter. If you could possibly email me at Jeremy@uslhs.org I would appreciate it.