Captain Joshua K. Card here, at Portsmouth Harbor Light near the mouth of the Piscataqua River in my home town of New Castle, New Hampshire. Today I want to tell you about Flora McNeil, a fascinating woman who had a career as a light keeper, businesswoman, and artist down in Connecticut.

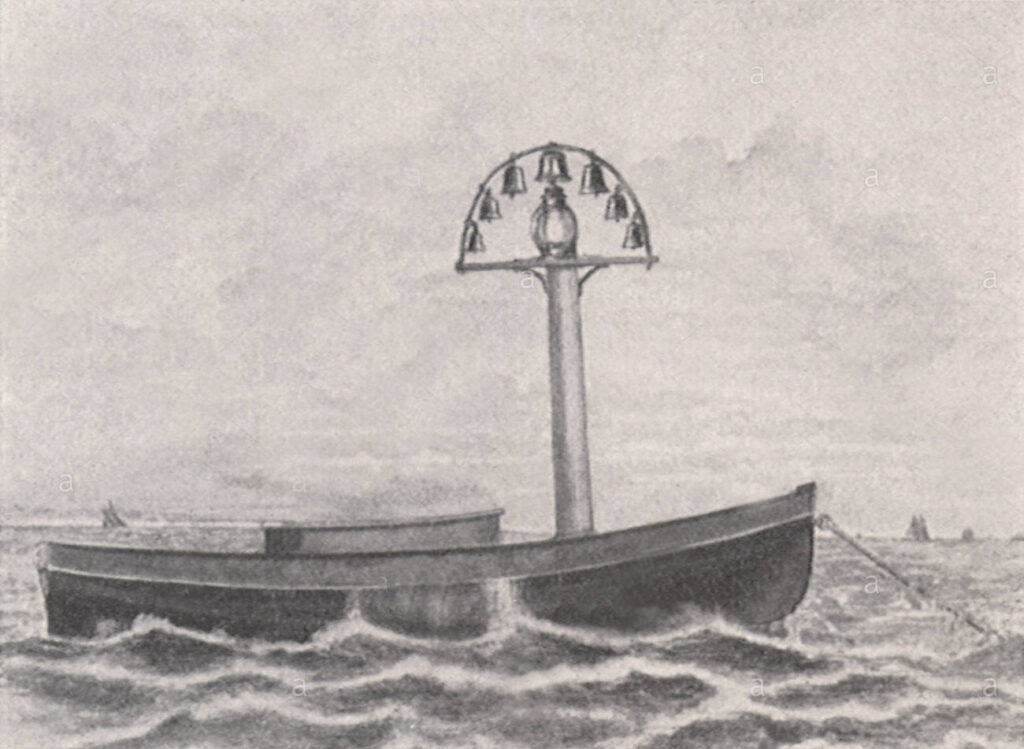

Bridgeport, the most populous city in Connecticut, grew up around a natural harbor at the mouth of the Pequonnock River. A tiny light boat marked the entrance to the harbor for a few years in the 1840s, and then a small iron-pile structure was erected in 1851. A keeper had to travel back and forth from shore to tend the light. Finally, in 1871, a proper lighthouse was established; it took the form of a handsome wood-frame dwelling with a cast-iron tower mounted at one end of its mansard roof.

S. Adolphus McNeil became keeper in 1876 and remained for the next 26 years. McNeil was a single man until 1886, when he married Flora Evans, who had made several long voyages with her sea captain father and was well versed in navigation. An 1887 article in the Bridgeport Standard described the McNeils’ life at the lighthouse:

Mrs. McNeil “paddles her own canoe” to [the] mainland . . . and besides perfecting herself in music from a competent teacher, devotes a considerable portion of her time to landscape and marine painting. She has in her parlor a fine upright piano and a violin resting in a corner of the room invites her deft fingers to produce its sweetest tones. Altogether Capt. McNeil’s home is a cozy and desirable one, too quiet perhaps for most people, but he is satisfied that he is in better quarters than he would be in the finest palace on land. He says he remained ashore one or two nights some time ago, but the incessant crowing of the roosters kept him awake and it was a relief to get home again.

For a few years S. Adolphus McNeil was given the additional duty of caring for Tongue Point Light at the entrance to the inner harbor. In 1901 he moved ashore to devote himself to that light. Tending the little cast-iron lighthouse on the breakwater was easy enough in fair weather, but walking out on the breakwater or reaching the station by boat could be hair-raising in heavy seas or fog, in spite of the addition of a landing wharf in 1896 and a plank walkway on the breakwater in 1900.

S. Adolphus McNeil died in December 1904 and was replaced by Flora at a salary of $300 per year. “When he died I asked for it,” she was quoted as saying in a newspaper article, “and although they were already giving up the idea of allowing women to become lighthouse keepers they knew that I had actually been the keeper of the light for twenty years and I was allowed to retain it without even an examination.”

A 1913 article described Flora McNeil bundled in a rubber coat, hat, and high rubber boats, scurrying along the plank walkway on the breakwater to reach the lighthouse through high wind and rain. She downplayed the hazards of the job:

As a rule, there is nothing really interesting about the work. Of course, during a heavy storm it isn’t exactly fun to take a trip out to the lighthouse, but the light must be going and the worse the weather the more necessary for it to be going. . . . Usually it is simply a matter of going out at sunrise to turn off the light and at sunset to light it. If there is a storm or a fog the bell, too, must be turned on. I have gone out in the middle of the night to start the fog bell, but as a rule I have had someone go with me.

The work, however, could be dangerous at times, according to Flora:

I think perhaps the hardest trips are the ones made in winter when it has rained and turned cold for the plank is then a glare of ice and naturally very slippery. I have been out during snowstorms when the plank was so slippery it was scarcely possible to keep your footing and when the storm was so heavy that all you could see in front of you was the falling snow. You could hear the roar of water under your feet and see the snow melt as it touched the waves but you could hardly more than guess where to put your next step.

Flora McNeil lived at 61 Lafayette Street in Bridgeport. She ran a manicure business in the Meigs Building, practically leading a double life as a well-dressed businesswoman by day, dedicated light keeper in her off hours. An expert boater, Flora claimed the sea never frightened her.

It isn’t exactly a pleasure to take a trip out there when a fog is coming on or when a heavy snow is falling with it so dark you can hardly see your hand before your face. You can hear the moaning water on either side of you and if you were on some desert island you could not feel more alone and forsaken by all humanity. There is not a sign of human life, the wind whistles and moans, the waters lap the rocks wildly and the rain beats into your face.

I suppose some people would think it an impossible thing to do—and probably it would be impossible for them—but I am almost as much at home on or in the water as I am on land and I have no real fear of the water even when it is angry.

Flora McNeil was keeper until 1920. The light was automated in 1954. The Coast Guard proposed discontinuing the light and fog signal in 1967, but local protests saved “Bug Light,” as it’s known locally. Today the solar-powered light, flashing green every four seconds, continues as an aid to navigation. The lighthouse is adjacent to the grounds of the Bridgeport Harbor Generating Station.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org