Captain Joshua K. Card here, at Portsmouth Harbor Light, New Hampshire. I’m thankful to have had a long career at a mainland light station in a beautiful little town — my home town of New Castle. I never served at an offshore caisson light, and I don’t envy those who did. I think the round walls would have driven me bonkers. More than that, the isolation, particularly in winter, would not agreed with the sociable aspects of my nature.

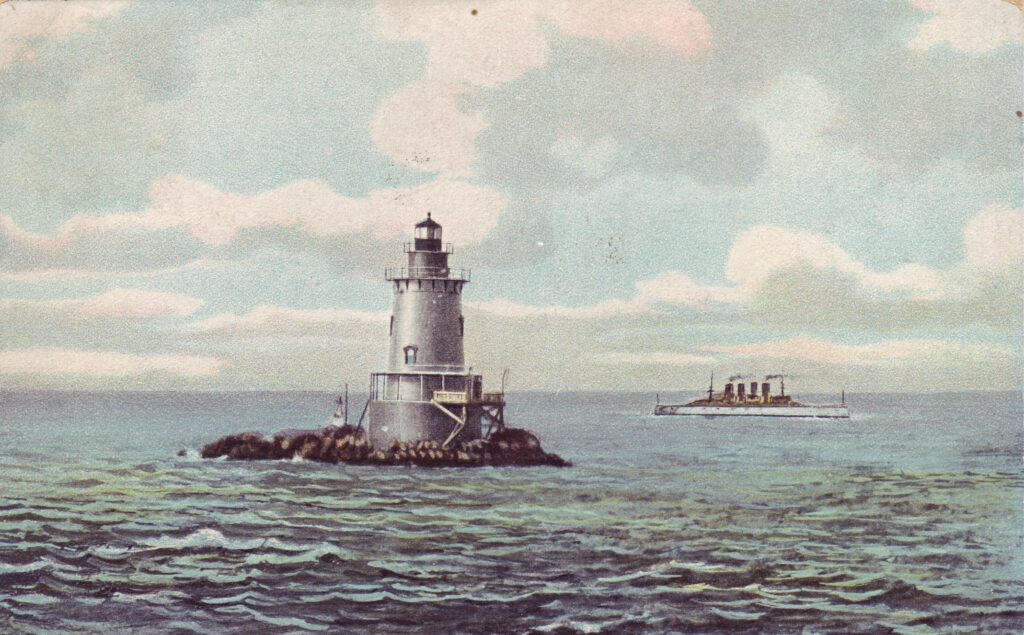

Great Beds Lighthouse is a cast-iron caisson tower a few feet on the New Jersey side of the border with New York at the mouth of the Raritan River between South Amboy, New Jersey, and Staten Island, New York. The light went into service on November 15, 1880, and in June 1898, a 1,227-pound fog bell was added, with machinery striking a double blow every fifteen seconds. The first keeper was David C. Johnson.

In April 1883, the New York Times reported that the keeper, George Brennen, had been missing for several days. Brennen had gone to the custom house in Perth Amboy to pick up his pay and then accompanied friends to South Amboy. He started back in his rowboat for the lighthouse early in the evening, but residents on shore noticed that the light wasn’t lit that night. The keeper’s overturned boat washed up on the beach the next morning. It was reported that he was “of sober habits,” and the reason for the capsizing of the boat wasn’t clear. Brennen’s body was eventually found.

Just four months later, on August 28, 1883, the New York Times reported that Brennen’s replacement, John E. Johnson, had been missing for ten days. He had last been seen on duty at the lighthouse on August 18, and his boat was found moored at the station. His coat was in the boat, and his keys were inside the lighthouse on a table. Some speculated that Johnson had committed suicide, while others thought that the keeper, who had a wife and four children, “disappeared for a reason.”

David J. Johnson, a Civil War veteran who was a relative of the first keeper, took over as principal keeper in 1894. Johnson lost his job four years later over a dispute with the assistant keeper, John Anderson. It seems that Johnson’s family was living at the lighthouse and consuming government rations without permission. Anderson was also dismissed for using “indecent language” in the presence of Johnson’s family.

In 1916, the keeper, Ellsworth J. Smith, after spending many lonely hours at the lighthouse, placed an ad for a wife in a local newspaper. The ad ran for three months before Helen Barry of New Haven, Connecticut, replied. Preparations began, but when Ms. Barry admitted she was only sixteen years old, the city clerk in Perth Amboy refused to grant a license. A newspaper reported that Smith was “steeped in gloom” but that he was determined “to find a wife yet.” He did find a wife, but the story ended in tragedy.

By 1922, Smith was the keeper at Conimicut Lighthouse near the mouth of the Providence River in Rhode Island. His 30-year-old wife, Nellie, had lived with him in the lighthouse for about a year, along with their two sons, aged two and five (or six, according to one account). On June 10, Keeper Smith went to Providence to take care of some business. The feelings that must have engulfed him on his return to the lighthouse are unimaginable.

According to a story the next day in the New York Times, Nellie Smith had grown “morose and despondent” during her year of lighthouse life. She had asked her husband to take her shore to live, and had threatened suicide. That day, while her husband was gone, Nellie found his keys and opened the medicine cabinet. She gave poison tablets to each of her sons, telling them they were candy. The older boy spit out the tablet, but swallowed enough to become ill.

Ellsworth Smith returned in his dory to the lighthouse around 6:00 p.m. He entered to find his younger son, Russell, lying dead on a table, and his wife dead in bed. The older boy, Ellsworth Jr., was in agony, and Smith rushed him ashore for medical assistance. Meanwhile, authorities were notified that the lighthouse had been abandoned and a warning was issued to shipping interests. After an antidote was administered, the surviving boy was taken to the home of the keeper’s sister to recuperate. It isn’t clear if Ellsworth Smith spent any more time at the lighthouse, but it seems doubtful.

When I hear people speak of the romance and adventure of lighthouse keeping, I would direct them to stories like those of Nellie Smith and George Brennen. Life at offshore, isolated lighthouses could be brutal and dangerous.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org