As discussed in my preceding column, by 1857 the Lighthouse Board introduced the Antebellum Standard Brick Tower Plan. Daniel Woodbury designed and built the first in this lighthouse class at Loggerhead Key.

At least four other engineers followed in Woodbury’s footsteps: Danville Leadbetter, George Horatio Derby, William Henry Chase Whiting, and Lorenzo Sitgreaves. Between them they used the standard plan as the basis for at least six lighthouses, plus a seventh planned lighthouse that was never built.

(National Archives via USLHS Digital Archives)

Danville Leadbetter was Woodbury’s classmate at West Point, graduating third. Leadbetter was assigned to several engineering projects in Mobile Bay during the 1850s, including improvements to Fort Morgan and the construction of Fort Gaines. He was also the first Engineer of the 8th Lighthouse District, in which role he is believed to have been the designer of the second lighthouse on Sand Island which stood 150 feet tall. This lighthouse included the attached oil house, but used simple iron brackets rather than a brick apron to support the gallery deck. Woodbury resigned from the Army at the end of 1857 to become Chief Engineer of the State of Alabama. He served in the Confederate Army and was buried in Mobile when he died shortly after the war. Woodbury’s handiwork was blown up by Confederate soldiers from Fort Morgan in early 1863. Although he had been assigned to Mobile Bay early in the war, by the time of the explosion he had be transferred to East Tennessee.

(Wikipedia)

George Derby succeeded Woodbury as 8th District Engineer. A graduate of the famous West Point Class of 1846 that produced 22 Civil War generals. Derby had been severely wounded in the Mexican War then worked on various surveys and engineering projects in the American West. He was an eccentric character who became a famous humorist writing for early California newspapers and magazines. Derby died in 1861, probably from a brain tumor.

During his time as District Engineer, Derby designed the the third Cape San Blas Lighthouse and probably the second Pensacola Lighthouse (there’s a possibility Danville Leadbetter designed Pensacola simultaneously with Sand Island). Both included the attached oil house. Pensacola used the flared brick apron while Cape San Blas used the simple brackets, although its original design had also used the brick apron. Pensacola is still active today, but Cape San Blas succumbed to the cape’s relentless erosion.

(National Archives)

W. H. C. Whiting graduated first in the West Point Class of 1845. After serving on various engineer and survey projects on the Gulf and Pacific Coasts, he was transferred to the South Atlantic Coast in 1856. There he succeeded Daniel Woodury in supervising work on Forts Caswell and Macon. He also supervised work on Fort Clinch in Fernandina Beach, Florida and Forts Pulaski and Jackon in Savannah, Georgia. Whiting was also superintending engineer of several river navigation improvement projects and Engineer of the 6th Lighthouse District.

Whiting designed at least three lighthouses: the third St. Johns River Lighthouse near Jacksonsville, Florida; the first Hunting Island Lighthouse, South Carolina; and the second Cape Lookout Lighthouse, North Carolina. Shortest of all lighthouses following the standard plan, St. Johns River had a one-story attached oil house. This lighthouse survives at Naval Station Mayport, albeit without its oil house and with its base slightly buried. The first Hunting Island Lighthouse in South Carolina. It was essentially identical to Woodbury’s second Cape Romain Lighthouse, but did not survive the Civil War. As designed, the second Cape Lookout Lighthouse adds the first floor cellar of the Romain/Hunting design, but otherwise follows the standard plan. However, like Loggerhead Key, it ended up being built without any attached oil house.

Whiting also submitted two proposals for a new first-order lighthouse at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. One design was essentially the same as the Cape Lookout Lighthouse (as built). The other design closely resembled the one-story oil house version of the standard plan, except that it featured decorative iron gallery deck brackets very similar to those used in postbellum lighthouses. Neither design would be used thanks to the intervention of the Civil War. A replacement for the Bald Head Island Lighthouse would not be built until the turn of the century.

(Wikipedia)

W. H. C. Whiting resigned from the Army at the start of the Civil War. He served at Charleston Harbor then in Virginia before being reassigned to Wilmington, North Carolina in 1862. There he designed, built, and commanded Fort Fisher. Wound and captured during the Union assault on the fort in January 1865, Whiting died of dysentery while a prisoner of war.

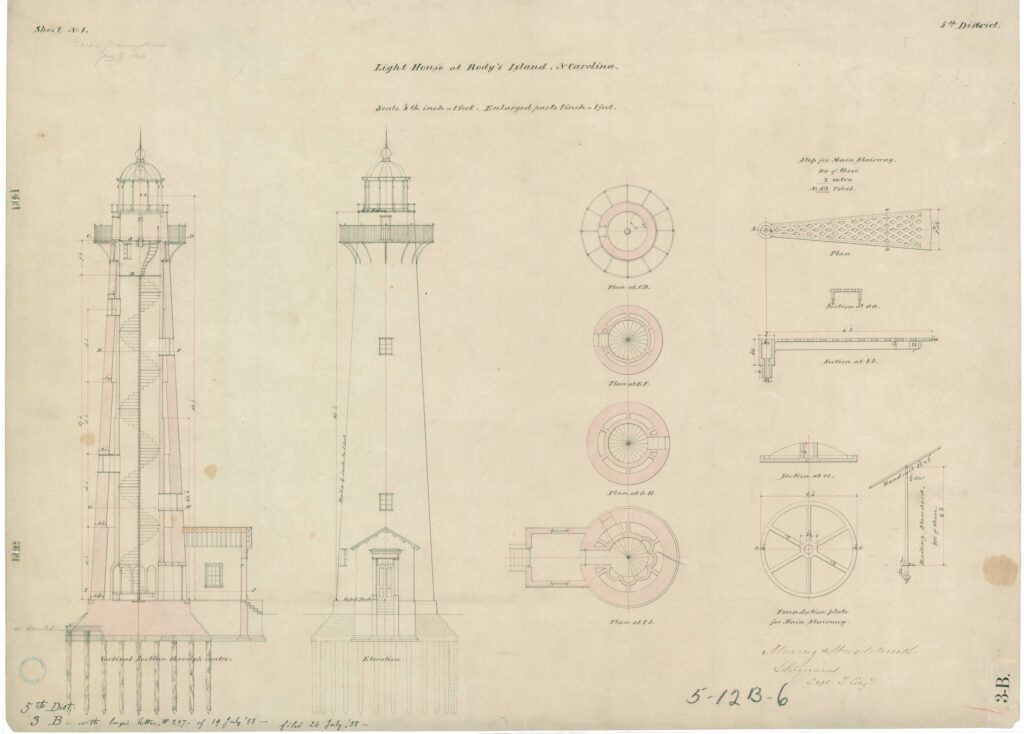

Lorenzo Sitgreaves, 5th Lighthouse District Engineer (1857-1859), used the standard plan to design the second Bodie Island Lighthouse. He used the one-story oil house and simple iron bracket variant, and also included alcoves for oil butts inside the base of the tower.

(National Archives)

Ironically, the creation of a standardized brick lighthouse plan in the mid-1850s did not result in a true standardization of the actual lighthouses as the engineers continued to tinker. Nevertheless, the inter-related designs of Woodbury, Leadbetter, Derby, Whiting, and Sitgreaves were part of a period of significant expansion by the Lighthouse Service. Many of these lighthouses fell victim to the Civil War. However, the long survival of Pensacola and Cape Lookout (and Woodbury’s Loggerhead Key) suggest this class of lighthouses would have mostly stood the test of time had the war not interfered.

Next time we’ll look at what the post-Civil War era wrought for brick lighthouses.

Josh Liller is the Historian and Collections Manager for Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse & Museum. He also serves as a Historian for the Florida Lighthouse Association. He is co-author of the revised edition of Five Thousand Years On The Loxahatchee: A Pictorial History of Jupiter-Tequesta, Florida (2019) and editor of the second edition of The Florida Lighthouse Trail (2020).