The Civil War was an important event in the history of lighthouse design. Many Southern lighthouses that would otherwise have been in service for a long time, probably even standing today, were destroyed during the conflict. The need to rebuild created new opportunities to innovate and improve. The lighthouse engineers of the 1850s had nearly all moved onto other things by 1866. Some of the postwar engineers gained extra engineering experience during the war. Although West Point graduates would serve on the Lighthouse Board and as District Engineers until 1910, the disruptions from the war would also give several civilian civil engineers a chance to make a difference.

By the 1860s, brick lighthouse design had seemingly settled on certain features:

- double-walled conical towers, with buttresses between the walls

- iron staircases around a central iron column had largely superseded wooden stairs around wooden columns (stone stairs were still occasionally used)

- railed gallery deck around the lantern rather than the narrow, unsafe ledge of the old “birdcage” lanterns

Other questions that seemed unresolved:

- should the gallery deck be supported by flared/corbelled brick, iron brackets or stone brackets?

- should oil butts/casks be stored in alcoves inside the base of the tower, an attached oil house, or a detached oil house?

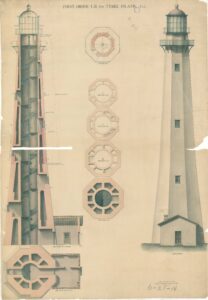

The first glimpse of what post-war brick giants might look like came at Tybee Island, Georgia. In 1860, the lighthouse there was a single-walled octagonal relic of of the 1770s. (It’s unclear if the tower was a lighthouse from the beginning, or if had only been lighted after the American Revolution.) It became a casualty of the Civil War, being partly blown up by retreating Confederates before it fell into Union hands in 1862.

William A. Goodwin, a civil engineer assessing lighthouse damage, concluded the tower might be salvageable. Jeremy P. Smith, another civilian who served as 6th District Engineer (1864-1868), submitted a design in Feb 1866 for the Tybee Island Lighthouse that stands today. Smith added a cylindrical inner wall, with buttresses connecting it to the surviving octagonal outer wall. The upper portion of the tower had to be rebuilt entirely. A small oil house was added the the base of the tower. Simple iron brackets supported the gallery deck. A railing encircled a smaller catwalk around the lantern glass. The lantern had three rows of square glass panels, topped with a semi-circular roof. A circular ball vent kept rain out of the chimney. The design was not a radical departure from antebellum designs, but is probably the first glimpse of postbellum design.

Meanwhile, the most important question facing the Lighthouse Board was how to replace the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The Diamond Shoals have always been one of the greatest natural hazards on the Atlantic Coast. Although the lighthouse had survived the war, it was insufficient even after improvements in the 1850s. For the light to reach far enough out to sea, Cape Hatteras would need to have the tallest lighthouse ever built in the United States, standing nearly 200 feet. Designing that task fell on the shoulders of another civilian engineer, William J. Newman (5th District Engineer, 1861-1868). The resulting design not only accomplished its goal as an aid to navigation, but proved so well-built that it could be safely moved more than a half mile in 1999 to save it from the encroaching ocean.

(National Archives via USLHS Digital Archives)

Where Jeremy Smith’s design had essentially played it safe (other than incorporating the remnant tower), Newman took his design in some new directions. Yes, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is a double-walled conical brick tower, but with an octagonal base – perhaps the best of both worlds for stability and wind resistance. Continuing the back and forth engineering debate about oil storage, Cape Hatteras eschewed an attached oil house for three large alcoves in the base of the tower.

In the center of base was a “weight pit” – probably the first such use in a lighthouse. This small pit in the center of the ground floor could be filled with sand and serve as a soft landing spot for the weight that rotated the Fresnel lens if it descended all the way to the ground or if the cable holding it snap. Newman’s iron gallery brackets dispensed with the simple design of Tybee and its antebellum predecessors. The brackets used appear more ornate yet are also probably sturdier.

Note the gallery bracket design.

(Illustration by John Havel,

USLHS Digital Archives)

Immediately below the lantern is a service room, a feature found in few previously lighthouses (Cape Ann, Montauk Point, and Pensacola are antebellum examples). Rather than windows on all four sides of the tower as many 1850s lighthouses had, Cape Hatteras has its large and well-framed windows on only two sides – above the door and opposite the door. These area also the sides aligning with the center of the landings. Gone was the central column for the stairs, a staple of nearly every previous lighthouse. Instead, the tower featured broad semi-circular iron landings on alternating sides. Connecting each landing was a double-railed staircase along the wall that made a single rotation of the tower between each landing. Practically every visitor who has climbed Cape Hatteras Lighthouse has been grateful such a tall lighthouse has such manageable stairs and such broad landings at which they can stop to catch their breath.

Given Cape Hatteras’ fame, credit for its design has long been a topic of interest. Historian John Havel and the National Park Service both credit Newman, and this corresponds with his time as district engineer. The “smoking gun” is now available thanks to digitization efforts by the National Archives. What appears to be the first draft of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s design bears the handwritten note “Project for a new light house at Hatteras. Submitted with letter of Mr. W. J. Newman, Actg. Engr. 5th L.H. Dist. Dated Jany. 31St 1868.” The design clearly underwent some changes before it was finalized, probably due to feedback from the Lighthouse Board and particularly Engineer Secretary Orlando M. Poe (who will be the subject of a future column).

It would be interesting to know more about Jeremy P. Smith and William J. Newman. Obviously, civilians were hired due to a wartime shortage of Army engineers. But what kind of background did these men have and what other projects did they work on? Tybee Island and Cape Hatteras stand as testaments to their engineering skill, but the rest of their stories for now remain a mystery.

Josh Liller is the Historian and Collections Manager for Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse & Museum. He also serves as a Historian for the Florida Lighthouse Association. He is co-author of the revised edition of Five Thousand Years On The Loxahatchee: A Pictorial History of Jupiter-Tequesta, Florida (2019) and editor of the second edition of The Florida Lighthouse Trail (2020).