Kate Walker here, keeping the light on Robbins Reef.

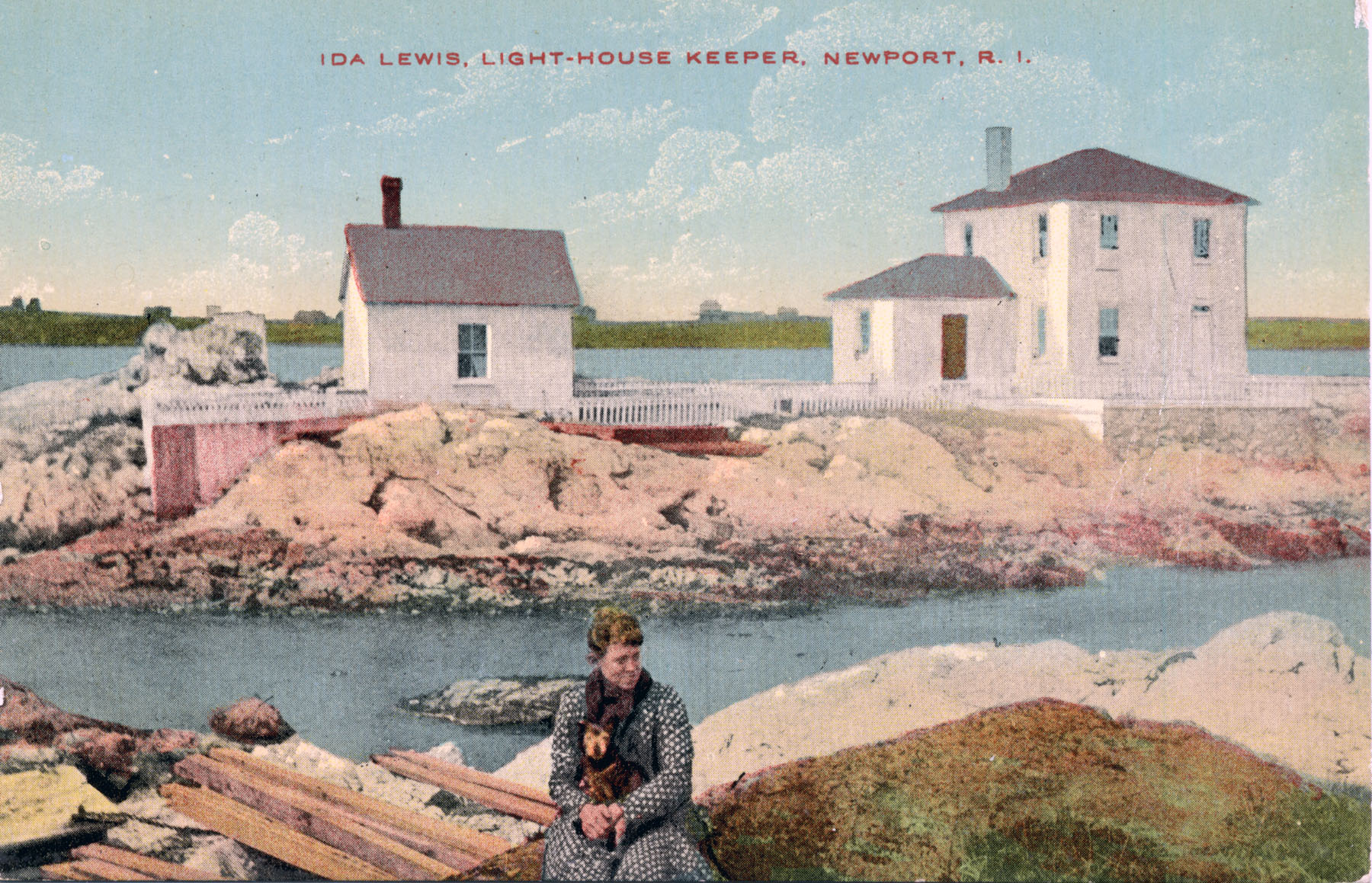

I think I’ve already mentioned that only a few visitors came to Robbins Reef because they had to come by boat, tie up, and climb my ladder. At other lighthouses that were more accessible, visitors came, often in large numbers. Fame for her rescues of drowning seamen brought visitors to Lime Rock in Newport, Rhode Island, to stare at Ida Lewis. Her wheelchair-bound father entertained himself by counting their numbers — often a hundred a day; nine thousand in one summer alone. The lamp and lens were located in an elevated closet, raised a step or two and reached by a door from the hall. Visitors actually walked through the family’s living quarters to see the light.

The 1881 Instructions to Light Keepers tells keepers that visitors to a light station were to be treated courteously and politely, but not allowed to handle the apparatus or carve anything on the lantern glass or tower windows. This meant that visitors could not be allowed in the lantern without a keeper in attendance. Reaching the lantern at Stony

Point Lighthouse on the Hudson River involved three sets of steep steps and unlocking doors and trapdoors. Keeper Nancy Rose and her children found the repeated climbing of the stairs and the supervision of large numbers of park visitors trying.

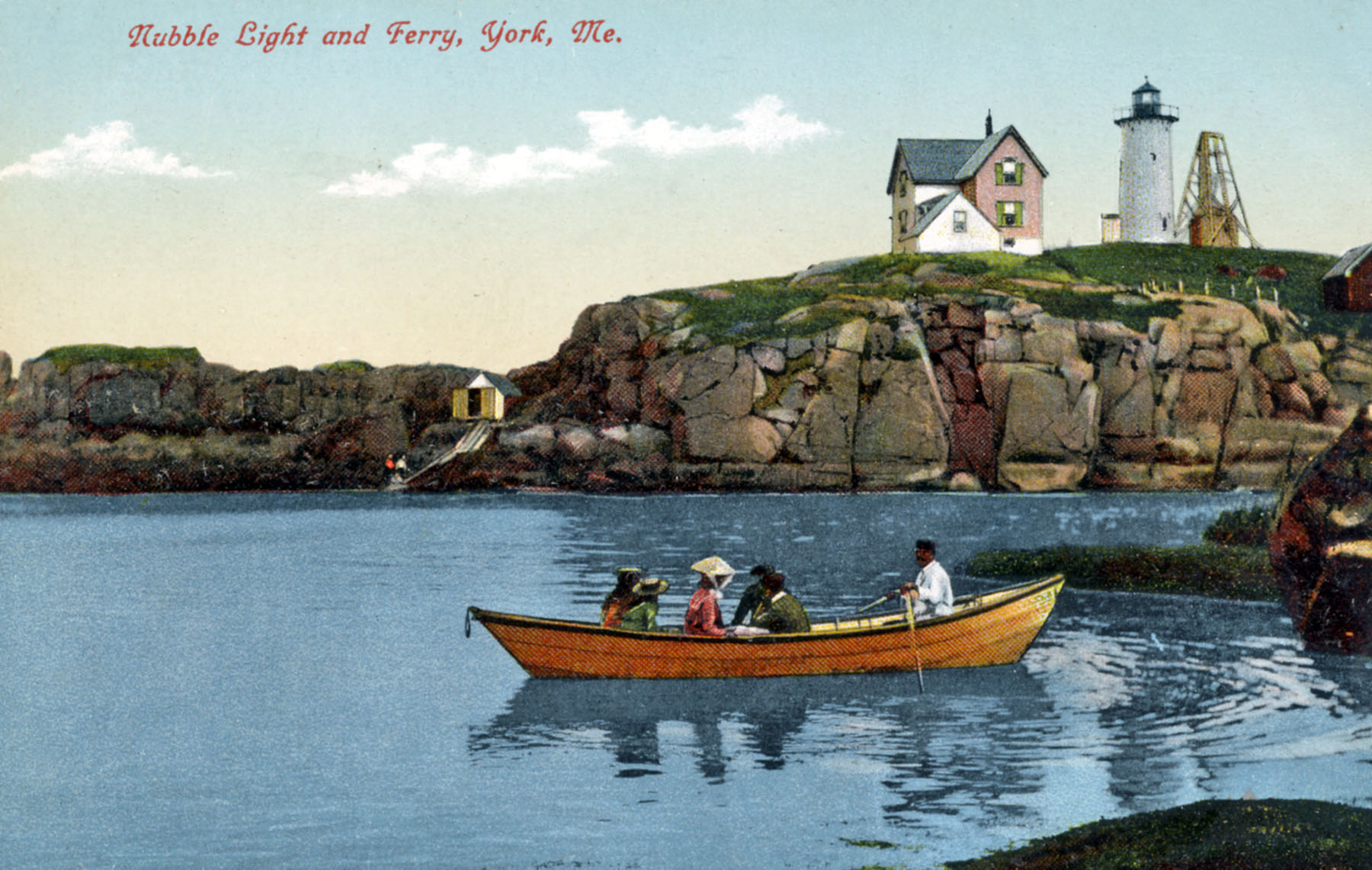

James McCobb, keeper at Burnt Island Light Station in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, wrote in his log on July 7, 1872, “Many strangers looking around the station.” By 1872, Maine had become a popular summer resort for people who could afford to build cottages there, as well as for patients who stayed at pleasant onshore resorts. The steamship companies saw a growing market of less affluent day-trippers, who enjoyed cruising among the many islands and stopping for a picnic and walkabout. A lighthouse was splendid entertainment — a novelty, and a tour of the premises cost nothing.

On April 13, 1876, McCobb wrote in his log, “All who can are leaving the cities and country back of us are coming to the seashore to enjoy the sea breezes. Very many are visiting this station daily. Some days more than 100 have called and in fact so many that they are becoming a real burden, taking up half my time to wait upon them.”

By August 29, 1878, McCobb’s patience had run out. “Much company here today to see the Light House and to make themselves troublesome generally as they could. Wish the Board would issue one more regulation, and that would be that no more strangers could be admitted into the lantern under no consideration.”

Instruction 18. Keepers must not make any charge, nor receive any fee, for admitting visitors to light-houses.

William Brooks took over as keeper of Cape Neddick Light Station in Maine in 1904. He charged 10 cents to visitors who came to the island; for another 5 cents they could tour the keepers quarters. When the district inspector learned of these activities, the keeper resigned.

St. Augustine, Florida, grew as a tourist destination and the lighthouse became increasingly popular among the city’s visitors. In 1901 Keeper Peter Rasmussen reported 1,500 visitors. By 1912 the figure had risen to 8,500, with 5,500 visitors already in the first three months of 1913. He concedes that these numbers are likely inaccurate because “as easily one-fourth gets away with not registering, it being impossible to watch all of them.”

Information is from Women Who Kept the Lights; 1881 Instructions to Light Keepers; and Keeper James McComb’s and Peter Rasmussen’s logs.

U.S. Lighthouse Society News is produced by the U.S. Lighthouse Society to support lighthouse preservation, history, education and research. Please join the U.S. Lighthouse Society if you are not already a member. If you have items of interest to the lighthouse community and its supporters, please email them to nelights@gmail.com.

U.S. Lighthouse Society News is produced by the U.S. Lighthouse Society to support lighthouse preservation, history, education and research. Please join the U.S. Lighthouse Society if you are not already a member. If you have items of interest to the lighthouse community and its supporters, please email them to nelights@gmail.com.

Candace was the US Lighthouse Society historian from 2016 until she passed away in August 2018. For 30 years, her work involved lighthouse history. She worked with the National Park Service and the Council of American Maritime Museums. She was a noted author and was considered the most knowledgable person on lighthouse information at the National Archives. Books by Candace Clifford include: Women who Kept the Lights: a History of Thirty-eight Female Lighthouse Keepers , Mind the Light Katie, and Maine Lighthouses, Documentation of their Past.