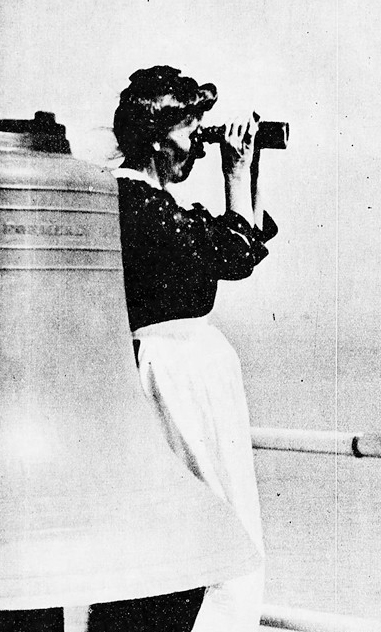

Kate Walker here, keeping the light on Robbins Reef on the edge of New York Harbor.

Fog was frequent at Robbins Reef. When I saw it coming, I went down into the deep basement and started the engine that sent out siren blasts from the fog signal at intervals of three seconds. What a huge advance from the cannon that was used as a fog signal at Boston Harbor 200 years ago. Fog bells run mechanically were introduced in the early 1850s. They were operated by a striking mechanism and weight that was raised by either a flywheel or clockwork. Steam-powered whistles were introduced in the late 1850s. In 1866 the reed horn signal powered by a caloric engine was also introduced.

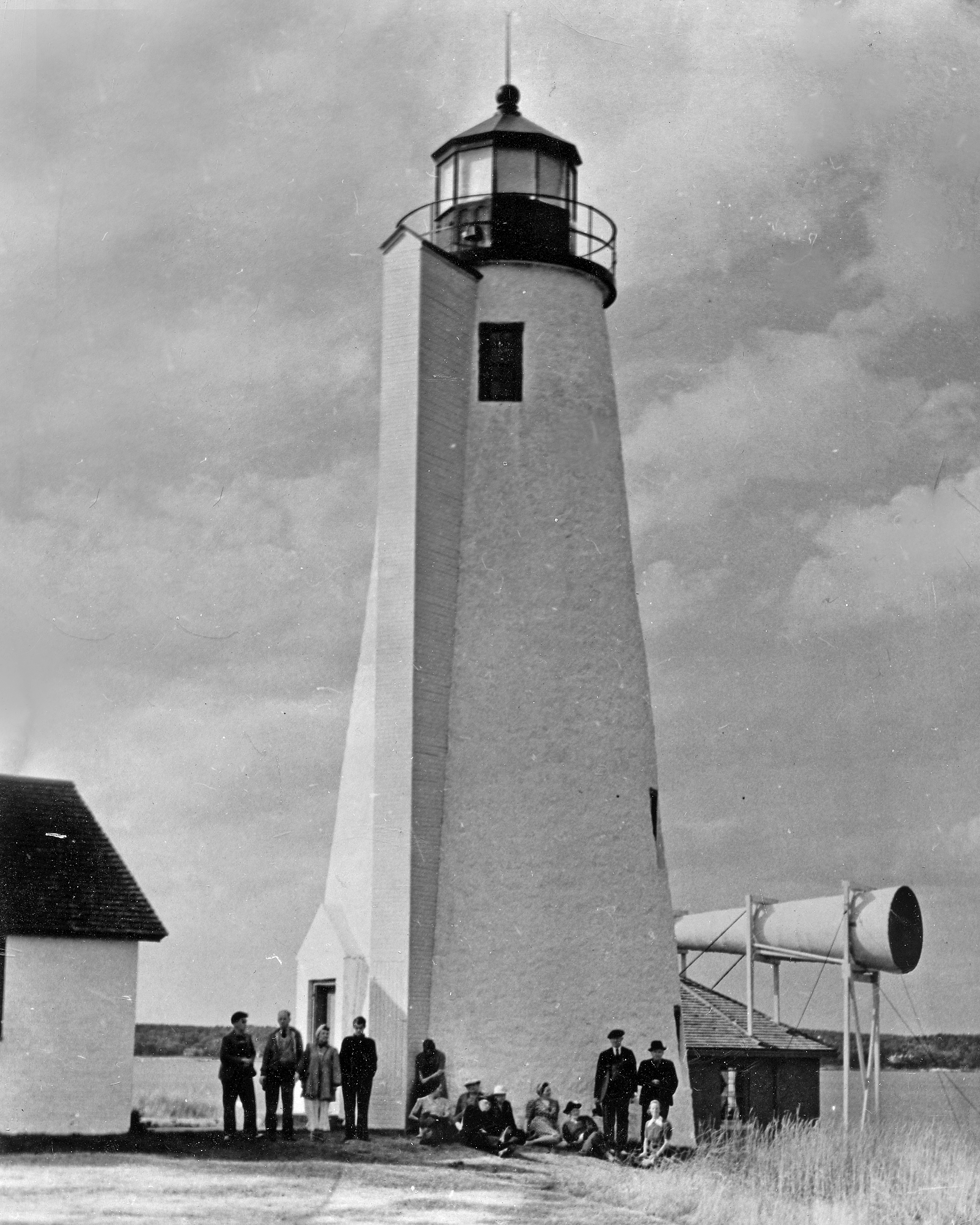

On April 25, 1893, our fog bell was removed and a blower siren was installed, operated by a Priestman engine. This engine only lasted for a few years before a Hornsby-Akroyd oil engine replaced it in 1896. Two years later, a larger trumpet for the fog siren was installed, and the fog-signal apparatus was overhauled and repaired.

The siren made so much noise that Jacob and I didn’t even try to sleep.

A siren installed at Alcatraz Light Station in San Francisco Bay caused a storm of complaints from residents who found it grating.

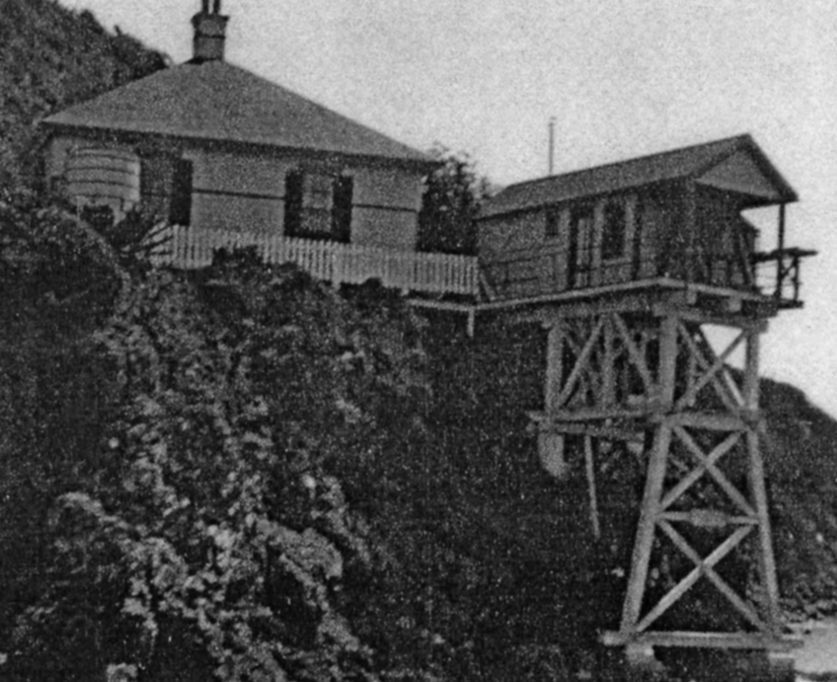

Juliet Nichols tended the Angel Island Light and Fog Signal Station in San Francisco Bay while I was at Robbins Reef. A new striking apparatus was installed on Angel Island in 1905. In 1906 Juliet was watching the fog roll in through the Golden Gate, as it regularly does, and listening to the fog signals start up in the lighthouses on both sides of the channel. She rushed to start her own equipment, only to have the machinery cough into silence. Juliet struck the bell by hand for 20 hours and 35 minutes.

Occasionally my fog horn machinery broke down, and then I climbed to the top of the tower and banged a huge bell. When the men at the nearby lighthouse depot on Staten Island heard the bell, they knew they must visit Robbins Reef and make repairs to the fog signal as soon as wind and weather permitted.

Mechanical fog bells were notorious for breaking down. The mechanical pounding of the bell produced strong vibrations, which caused tension bars and hammer springs to break, even snapping the rope attached to the clockwork weight. Juliet Nichol’s whole career at Angel Island [1902 – 1914] was a battle with fog. Her log recorded periods of fog as long as 80 hours at a time and the many times she was forced to strike the bell by hand.

On the fourth of July, 1906, the machinery [at Angel Island] went to pieces., the great tension bar broke in two and I could not disconnect the hammer to strike by hand. I stood all night on the platform outside and struck the bell with a hammer with all my might. The fog was dense, with heavy mist, almost rain.

What a way to celebrate Independence Day!

************

Information is from Clifford, Nineteenth Century Lights, p. 83; National Archives Record Group 26 Entry 1, Volume 755; Annual Report of the U. S. Light-House Board; National Archives Record Group 26 Entry 8 (NC-63); Clifford, Women Who Kept the Lights

Candace was the US Lighthouse Society historian from 2016 until she passed away in August 2018. For 30 years, her work involved lighthouse history. She worked with the National Park Service and the Council of American Maritime Museums. She was a noted author and was considered the most knowledgable person on lighthouse information at the National Archives. Books by Candace Clifford include: Women who Kept the Lights: a History of Thirty-eight Female Lighthouse Keepers , Mind the Light Katie, and Maine Lighthouses, Documentation of their Past.