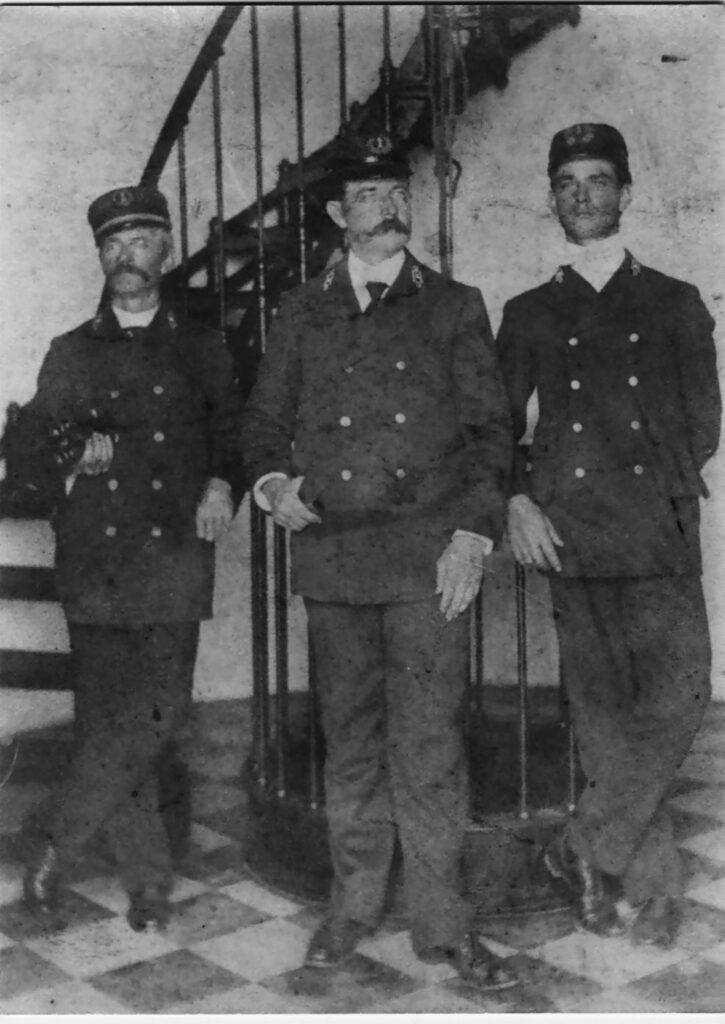

Thomas Patrick O’Hagan, Mosquito-Ponce Inlet Lighthouse’s second principal keeper (1893-1905), and principal keeper at Amelia Island Lighthouse (1905-1925), was stationed at many other U.S. Light House Service stations during his fifty year career. Two of his sons became keepers, and a third worked as a mate on USLHS tenders. O’Hagan has some fascinating stories to share about his life at different stations throughout his long service, his extensive contacts with keepers at other stations, Lighthouse Service officials, and of course, his sons’ and family members’ tenure at other stations in the Fifth and Sixth Districts.

John F. Mann, Lead Docent, Ponce Inlet Lighthouse and Museum

APRIL 3, 1927 Moderate to Light breeze, S.E. Cool. Showers early this AM. Too damp and chilly to sit out on the porch, so I’ll sit and write in my composition book here at the kitchen table. Well, looking back over what I wrote last week, I digressed again. I was supposed to be talking about our Amelia Island Lighthouse.

It started like this. Mr. Winslow Lewis first built a 65-foot tower in 1820 on the southernmost end of the Georgia’s Cumberland Island, just north of here, before the Government of Spain ceded Florida to the United States. In effect, the lighthouse was positioned there to mark the entry to the St. Mary’s River. Interestingly, for a year, it also marked the southernmost part of the East Coast of the then United States! Well, pretty much over the next fifteen years, the channel continued to shift southward and eventually the light could no longer be seen when entering the river. It became useless to mariners. And at this time, the folks here in Fernandina, merchants and ship’s captains, began to ask the Congress for a lighthouse to be built here on Amelia.

The decision was made in late 1838 to dismantle the Cumberland Lighthouse, brick by brick, and place it the highest spot on Amelia Island – which they tell me is 59 feet above sea level. At the same time they were disassembling our tower to move it, they were building a new sixty- foot tower on the northern end of Little Cumberland Island, a smaller island to the north of Cumberland Island. About eighteen miles separated the two light stations. The new Little Cumberland Island light, they also called it St. Andrews Light because it marked the entrance to the St. Andrews Sound and the Satilla River, was first lit in 1838 with a fixed signal to distinguish it from Amelia Island. If I’m not mistaken, one of my First Assistants at Mosquito, Victor Thelning, left Mosquito to become Principal at Little Cumberland Island about a year before I left Mosquito to come to Amelia. Good man.

The “new” Amelia tower was fifty feet tall with a lantern room of 14 feet, making the entire a structure 64 feet tall. The cost was about $7,000, and paid, again, to Lewis, the same Mr. Lewis who originally built the tower on the Georgia island in the first place. The Amelia tower was first lit on March 4, 1839. Even though he built about ninety of the nation’s early lighthouses, Mr. Lewis was controversial during the time Mr. Pleasonton was in charge of lighthouses for the Treasury Department and after. I don’t like to gossip, but it was well known that even Mr. Lewis’s own kin, his nephew, was very critical in a report to the Congress about his uncle’s lamp, his lighthouse construction and engineering, supervision, and his contracts to supply lighthouses. After visiting many of the Nation’s lighthouses the nephew said in his report that about half of the Lighthouse Establishment’s whole budget went for repairs, mostly to Winslow Lewis’s towers.

Critical was not the word used by most keepers and captains for Lewis. The first apparatus in the lantern at Amelia was a Lewis concoction of fourteen revolving lamps, backed by fifteen inch reflectors and fronted by a greenish magnifying glass. I never had to work with one, thank goodness. When I started as a temporary assistant at Hunting Island in 1876, our lens was a beautiful Second Order. Compared to Fresnel lenses, the Lewis Lamp was a nightmare to care for, and no keeper that I know of liked it. Eventually I.W.P. Lewis, the nephew, became known for designing some screwpile lights in the Keys and for advocating for the Fresnel lens. My Julia’s uncle, Amos Latham, was the keeper of the Cumberland, Georgia station, and followed it over here to become the first keeper at Amelia. Amos was a Colonial soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as keeper until 1842. His daughter, Jane Latham Donnelly, and her brother George Latham were also keepers here, but at different times. Amos Latham was first buried on the station grounds, and then reburied at the new town cemetery down the road.

I’m going to quit now, and go have lunch. I didn’t think I would like writing, but I do. It’s fun to remember some interesting times.

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org