Celebrating the Day Under Difficulties in Lonely Lighthouses, Lightships and Life Saving Stations – Houses of Refuge on the Florida Coast

By Arthur Budd

Edwardsville Intelligencer, November 22, 1922

[The following article is reproduced in its entirety. Although accurate in spirit, some of the details regarding lighthouses may not be precisely accurate. For more on the story of Abbie Burgess at Matinicus Rock, click here and here. The origin of the reference to insanity and suicides at Minot’s Ledge Lighthouse is unknown. And although the original 1850 tower at Minot’s Ledge swayed in storms and, in fact, collapsed, the present 1860 tower does not sway. Also, the version of the story of the Thanksgiving goose at Boon Island told here is fanciful. Here’s a telling that’s closer to what actually happened.]

On Thanksgiving Day, 1921, eleven persons, three of them women, narrowly escaping death by the shipwreck of a yacht in a autumn storm, managed to get ashore at a desolate spot some distance south of Jupiter Inlet, on the coast of Florida.

For so much they felt truly thankful, as well they might, but they had no notion where they were, and, unless they could find shelter, their peril was not yet over. To wander inland through the jungle of scrub palmetto and spiky “Spanish bayonet” seemed impossible, and so they walked northward along the beach. They discovered no sign of inhabitants; but suddenly after they had gone about three miles, they came upon a house.

It was a queer-looking house, substantially built of wood with a foundation of coquina rock (which is a conglomerate of little shells cemented together), and on the front door the words “Walk in!” were painted in large letters. But there was nobody home.

That seemed strange, because the little house, which had only three rooms, was provided with six iron single beds all made up and ready for occupancy, There was a big closet full of clothing hung on hooks in orderly fashion, and a store of foodstuffs in the main room, with a stock of fuel in a shed at the back.

Suggestion of the supernatural

It was the sort of thing one reads in a fairy tale. The mystery was explained, however, when the reading of a sign on the wall revealed that this tenantless home was one of many so-called “houses of refuge” which, scattered along the Florida coast where there are no life-saving stations, are regularly maintained by the Federal Coast Guard for the succor of shipwrecked people.

The Thanksgiving guests from the lost yacht were welcome to every comfort Uncle Sam could supply. The beds were for their use; the clothing likewise; for shipwrecked people are likely to need a quick change into dry garments.

Danger from Wind and Water

The lighthouses which guard the dangerous Florida reefs and submerged shoals along the Gulf coast are lonely places indeed. The characteristic type is a skeleton tower of steel which rises directly out of the sea, with a platform forty-five feet above the waves, on which the keeper’s house is built. Above the house is a great lantern, which is reached by a winding stair. Twenty feet below the main platform is the “cellar” of the house—a second platform used for storage purposes.

Some of these aquatic lighthouses are tall; others squat like gigantic spiders on the ocean. How anybody should be induced to live in them is a mystery; the keeper’s pay is only $750 a year. Once a year they are visited by a ship that brings supplies. Hurricanes are frequent in that latitude, and, when it nlows hard, the angry surges go rushing beneath the house, while the Wind Demon keeps up a continual roaring, with a voice so tremendous that the inmates are obliged to shout at the tops of their voices in order to hear one another in conversation.

Yet, doubtless, the dwellers in those lonely watch-towers of the sea have their own reasons for thankfulness when the annual holiday season arrives. At all events, they have not been swept away and drowned—as happened to some light keepers and their families in 1906, when, between the mouth of the Mississippi and Mobile (Ala.), no fewer than forty-four lighthouses, struck by a tidal wave, were either uprooted bodily and toppled into the ocean, or so rocked and twisted as to be practically destroyed.

Life Savers Turn Fishermen

Generally speaking, the regular life-saving stations of the Coast Guard are closed down and vacated by their crews in the summer time, because storms are rare at that season. Thus in summer the professional “surfmen” along the ocean front of North Carolina are mostly engaged in fishing. In fact, it is from the ranks of the fishermen (though some of them are sailors) that the life-saving service gets most of its recruits.

A glance at a map of North Carolina will show how the mainland is separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a series of wide “sounds,” the outer boundary of which is a narrow strip hardly more than a mile broad, that stretches like a barrier reef for a distance of 250 miles. This strip, which makes an oblique angle at Cape Hatteras, is the most dangerous part of the Atlantic coast, and is fairly fringed with life-saving stations.

Parted From Their Families

By Thanksgiving Day the season of storms in hat storm-beset region has begun, and a constant lookout must be kept for vessels in distress. There is no sure safety for the life-savers themselves. The sand strip is not a proper sense terra firma, but is constantly shifting, so that the men must be ready to take to their boats at any time. On one occasion, during a raging hurricane, five of the stations were actually turned upside down.

As may well be imagined, the dreary and inhospitable strip is no place for women to reside. Their presence is an impossibility, and so the homes of the surfmen are on the mainland, distant from the station by twenty-five miles of water in some instances. The only means of communication is by sailboat, and often it happens that this is cut off for weeks at a time.

The men are allowed in fair weather to shoot and fish, so long as they do not go beyond signaling distance, and by this means good things to eat are usually obtained for the Thanksgiving table. But the good wives on the mainland may be counted on, unless obstinate storms prevail, to contribute cooked turkeys, cranberry jelly, and other delicacies appropriate to the holiday for the enjoyment of their men folks o the desolate strip of sand.

All Stations Are Not Lonely

Some of the life-saving stations, situated elsewhere, enjoy much more cheerful conditions. Located on the mainland, little villages have been built up about them, The life guards and their families have opportunities at social enjoyment even in the winter time, and for the small community Thanksgiving is a proper occasion of festivity and rejoicing.

Most of the stations, however, are in more or less desolate places, and among the loneliest of them are those on Cape Cod and along the south shore of Long Island. There is one, situated on Muskeget Island, near Nantucket, which in winter is sometimes shut off by ice for week from the rest of creation. Several of those on the Great Lakes are as badly off—for instance, the station on Manitou Island, at the upper end of Lake Michigan, which frozen in, is often out of touch with civilization for long periods.

If the proper celebration of Thanksgiving be difficult at many of the life-saving stations, what shall be said of the lonely lighthouses? Consider the situation of some of them off the New England coast. Built on desolate rocks—Boon Island is one of these—they are sometimes cut off for months together from communications from the mainland.

Twenty miles out in the ocean, on the track of ships voyaging from Boston to Eastport and Halifax, is Matinicus Rock, a rugged and inaccessible islet on which no landing can be made except under unusually favorable weather conditions. On one occasion the keeper and his son had gone to the mainland for provisions, and storms prevented their return for three weeks. An invalid wife and three young daughters kept the light shining during all that period, which included Thanksgiving Day. Starvation threatened them; and what do you suppose they had for their Thanksgiving dinner? A cup of cornmeal gruel apiece. The eldest daughter afterwards married a young lightkeeper who was sent to take her father’s place. Later on, he got another job, and she of course, went with him. She had lived twenty-two years on that barren, sea-swept rock!

The Goose That God Sent

But speaking of Boon Island, the writer nearly forgot to tell about a little girl, four years old, daughter of the light-keeper there, who was in great distress because, owing to bad weather, her father had not been able to send for the customary Thanksgiving bird—not a turkey, but a goose. She knelt down outside the lighthouse and prayed God to provide a goose. And what do you suppose happened? A big wild goose in full flight struck the lighthouse and fell dead almost at her feet! She dragged it into the family dwelling by one leg, crying, “God has sent us our Thanksgiving dinner!”

Not far from Boston a tall tower of stone rises directly out of the sea, its foundations being laid in a submerged rock called Minot’s Ledge. In winter the tower is often swayed by the force of the waves like a tree in a storm, and sometimes it is cut off from communications with land for months. Several of its keepers have gone insane from sheer loneliness and two have committed suicide.

“Ships That Never Sail”

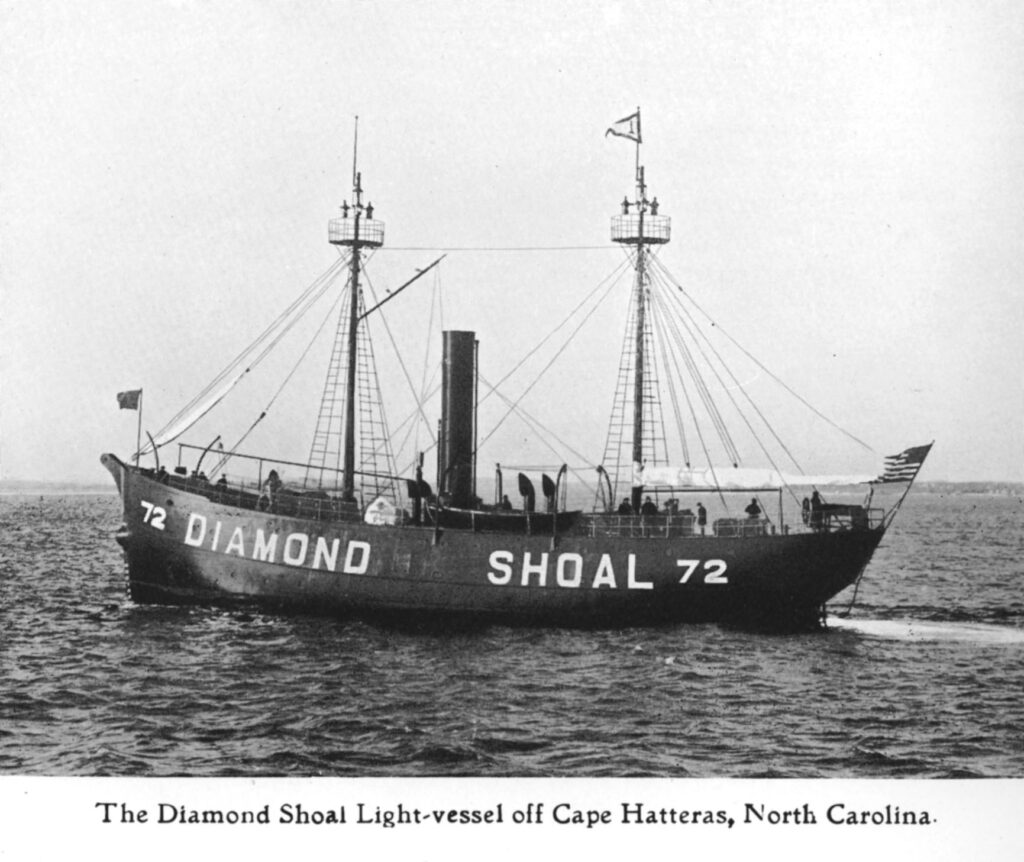

Fifty lightships are used by the Coast Guard to mark shoals off our coasts where the erection of lighthouses is not practicable. There are more of them about Cape Cod than anywhere else. Anchored with iron cables, they sail like the phantom ship, voyages without end, constantly buffeted by storms. Perhaps the worst situation of any of any is that of the lightship that guards Diamond Shoal, a variable graveyard of vessels, off Cape Hatteras. Thereabouts is the very abode of the Storm King, and not least of the perils is the demon fog which constantly prevails in winter, rendering the floating lighthouse to be struck and sunk by other craft.

No Thanksgiving turkey for captain and crew on a lightship. They may, however, be able to shoot a few ducks, which, supplemented by “plum duff,” the dish of luxury so beloved by sailors, will furnish forth a satisfactory feast to celebrate the holiday.

[Note: “Plum duff” has its origins in medieval England, and is sometimes known as plum pudding or just “pud,” but this can also refer to other kinds of boiled pudding involving dried fruit.]

Jeremy D’Entremont is the author of more than 20 books and hundreds of articles on lighthouses and maritime history. He is the president and historian for the American Lighthouse Foundation and founder of Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses, and he has lectured and narrated cruises throughout the Northeast and in other regions. He is also the producer and host of the U.S. Lighthouse Society podcast, “Light Hearted.” He can be emailed at Jeremy@uslhs.org